A burning question

A UVic graduate student smokes out the facts on the health risks of e-cigarettes

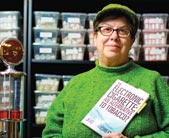

The small bottles on the counter

hold the “e-juices” used in

refillable e-cigarettes.

The device on the left

is a dispenser for e-juices.

PHOTO: Nik West

By Kim Westad

They’re the latest must-have accessory on the celebrity circuit, have their own slang language and are predicted to outsell conventional cigarettes within 10 years.

While electronic cigarettes—commonly known as e-cigarettes—have caught on in popular culture, they’re dividing the medical community.

Some view them as a way for cigarette users to gradually reduce their nicotine use and possibly save lives, while others see them as a gateway to increased cigarette use, opening the smoking—and addiction—door to new and younger users (and a clever way to circumvent no-smoking bylaws).

Lacking in all the discussion are objective reviews of the scientific studies that have been done on the devices, says University of Victoria graduate student Renee O’Leary. So O’Leary, who is working on her PhD at the university’s Centre for Addictions Research (CARBC), is doing just that.

“There’s little research evaluating them from a harm reduction point of view, looking at all the literature,” says O’Leary. “There are opinion pieces that are pro and con, but they’ve been done piecemeal. I’m looking at all the issues together to provide e-cig users and the public health community with hard data and accurate information.”

O’Leary is reviewing the 80 or so studies published in academic journals, looking at everything from the contaminants in the “e-juice” inside the e-cigarettes, to what precisely is in the vapour that the user inhales and exhales.

E-cigarettes have come a long way since 2006, when they were patented. Hon Lik, a pharmacist in China, invented them a few years earlier in an effort to reduce his father’s smoking. By September 2013, the company where Lik worked was sold to Imperial Tobacco for $75 million (US).

Now, there are an estimated 250 manufacturers worldwide, with sales of $3 billion in 2012.

All for a battery-operated device with a liquid-filled cartridge that heats when the person using it inhales, causing the flavoured liquid to vapourize. The carrier liquid of propylene glycol and glycerin is called “e-juice.”

In the US, that flavouring can legally include nicotine. Health Canada does not allow the sale of nicotine-filled cartridges, although they are readily available online and in some Canadian stores.

Smoking the e-cigarette is called “vaping,” a reference to the vapour. A tobacco cigarette is called an “analog.”

Many users say the vapour is harmless, but O’Leary is skeptical. While propylene glycol and glycerin are used in consumer products, they’re not usually heated as they are in e-cigarettes. The closest thing we have to that now is theatrical fog, which uses propylene glycol, O’Leary says.

“I don’t think it can be said that e-cig users are breathing out harmless water vapour.”

One study found that exhaled vapour contained acetone, formaldehyde, ultrafine metal particles and several other chemicals.

“My job as a researcher isn’t to form opinions or be an activist but to look at the data and provide clear information in a way people can understand to make their choices.”

View as PDF (560K).

E-cigarettes can be bought off the shelf in most Canadian stores. Health Canada does not allow the sale of nicotine for use in the devices. Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, Thailand and Brazil ban the sale of e-cigarettes altogether.

Forty per cent of current and former smokers 18 and over in Canada are aware of e-cigarettes and four per cent have tried them. Sixteen per cent of people aged 16 to 30 in Canada have tried one.

UVic’s Centre for Addictions Research (CARBC) is a network of researchers and groups dedicated to the study of substance use and addiction to inform improved public policy and support community-wide efforts to promote health and reduce harm. For more information visit www.carbc.ca

Renee O’Leary will be a featured speaker at IdeaFest, UVic’s annual celebration of knowledge and creativity, which takes place March 3–8. Her talk, "Electronic Cigarettes: What's The Buzz?" is on March 4, 4:30–5:30 p.m., in room C112 of the David Strong Building. The event is free and open to the public.