Literature and Physicality: Reflections on the Peter and Ana Lowens Fellowship

September 26, 2025

by: Sarah Evans, Lowens-Libraries Fellow

I find that in literary studies we can get stuck. I’ve just completed my undergraduate in English and Sociology, and, even in my greatest efforts at interdisciplinary studies, the most “unstuck” I achieved was combining statistical analysis and T. S. Eliot’s “The Hollow Men.” A fun paper to write, but still a paper. When I first learned about the Peter and Ana Lowens Fellowship through the University of Victoria’s Special Collections and University Archives, I saw a way to get unstuck. I’ve always believed that the work of the Humanities is to tell and preserve stories, but the constraints of an academic paper frequently inhibit this work. Stories create connection and powerful change, and they often leave something behind. Because of the Lowens Fellowship, I received the opportunity to explore one such story.

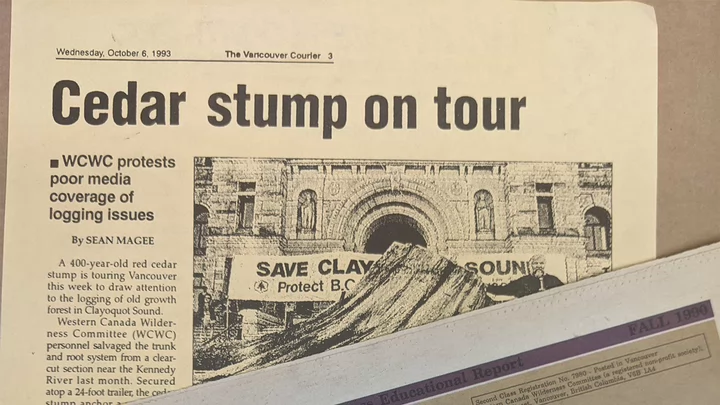

On Vancouver Island, our geography holds stories and people often have their own stories connected to the land. Clayoquot Sound’s 1993 "War in the Woods" is one of many intersections between people and geography in the Pacific Northwest. Much to my excitement, the University of Victoria Libraries house pieces of that story in Special Collections, including posters, chapbooks, news briefings, and photographs. In this pivotal environmental case, teachers, elders, poets, lawyers, accountants, and others, advocated for and acted on their values. In 2025, over thirty years after the BC government’s announcement to preserve a mere third of Clayoquot Sound’s old growth forests, we see this story’s legacy brough back into conversation in newer environmental management disputes. This research opportunity allowed me to review historical newspapers and see the photos taken by the people who were there. The project’s output was to bring Clayoquot’s archival materials out of the archives and reveal perspectival intersections between now and an increasingly relevant historical environmental moment.

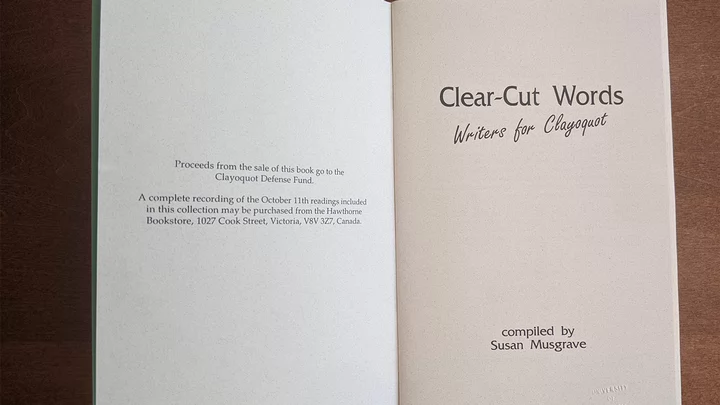

I had never considered the archives as a creative space. Before the fellowship project, I assumed archives were filled with records and files of little interest. With guidance from workshop leaders, we learned how archives come to life in printmaking, exhibitions, and paleography. There were more facets than I could dream of. My mentor, librarian Jessie Lampreau, graciously helped me weed through the overwhelming feeling of figuring out a place to start. There’s enough in Special Collections to keep you busy forever, I think. But, after the first plunge into the Clayoquot Resource Centre fonds, the topic crystallized. Creativity and voices exploded from the archives. These voices and perspectives were the way to get unstuck. As we rifled through boxes, folders, and books, the archives began to tell more sides to the Clayoquot story. Not only were activists deeply involved in the War in the Woods, but writers, including Robert Bringhurst, Dennis Lee, Al Purdy, Michael Ondaatje, Margaret Atwood, Edith Iglauer, and David Suzuki to name a few, were advocating for Clayoquot. In the unending desire to find relevancy in the humanities, these writers were not dithering over academic requirements but creating impactful art. After a whole degree of seeking impact, I found the story I was looking for in the archives. As the dust settled on my fingertips, I learnt how literature’s tangible products can create change to real geography.

In this project, the physical was the focus. Both in the sense of archives filled with material objects like newspapers and chapbooks, as well as in the physical impact these literary artifacts created on Clayoquot’s landscape. Creativity and literature appear ephemeral when we view them on computer screens or paperbacks. But here, in the archives, we see how literature creates lasting impacts. Often, we construct poetry and novels as things we hold for the duration it takes to read them, but, in Special Collections, these physical archives demonstrated how literary objects can impact landscapes. What I thought was a project on showcasing our environment through a case study, quickly evolved into a celebration of literature’s physical impact. Beginning from the literary artifacts in the fonds and continuing to the trees still standing in the Clayoquot biosphere, literature leaves its physical presence in the archives and the land it is embedded in.

Early in February 2025, I drove up the island to see the cedars that these works impacted. Going from touching the dust of newspaper pulp to standing under giants, I saw the work of literature as one that preserves. Looking back 30 years to the "War in the Woods," the impacts continue to ripple through British Columbia. Whether we create an archive or a protected region, the work in the humanities is to preserve—and celebrate. With huge thanks to Heather Dean, Jessie Lampreau, and the many faculty members who gave their time to teach us about the archives’ innerworkings, I am truly grateful to the opportunity given to me by the Lowens-Libraries Fellowship. Learning like this unravels expectations of literature’s contributions to the world beyond another academic article, and I hope that every student finds a way to get unstuck. Now, as I head off into my Masters in English, I’m beyond grateful that this project renewed my belief in the criticalness of creativity, even, if not especially, in academic contexts.