Protecting Generations

November 18, 2025

UVic’s Social Work faculty and alumni moved mountains to help communities reclaim child welfare, changing institutions and systems to reflect Indigenous ways of knowing and being.

For the past 16 years, Sqwulutsultun William Yoachim has been at the forefront of a push for Indigenous communities to reclaim their inherent right to care for their own children.

A member of Snuneymuxw First Nation, Yoachim is executive director of Kw’umut Lelum Child and Family Services in Nanaimo, a fully Delegated Aboriginal Agency under the Child, Family and Community Services Act.

An Indigenous agency rooted in Coast Salish snuw’uy’ulh (teachings), Kw’umut Lelum provides culturally driven family support, caregiving services and community programs and services to nine First Nations on Vancouver Island.

When a family is struggling, Kw’umut Lelum is called first to support parents and children. If children cannot live at home, their extended family and community are brought in to care for them.

“We have such a different narrative than mainstream child welfare,” Yoachim says. “Our stats are amazing. We have fewer kids in care—next to none. Things are done properly with consent.”

A former youth worker, welder, social worker and Nanaimo city councillor who graduated from the University of Victoria with a Bachelor of Social Work (BSW) in 2009, Yoachim credits UVic’s Indigenous child welfare specialization for strengthening Kw’umut Lelum’s work.

“UVic was bold enough to, back in the day, have an Indigenized specialization in the School of Social Work and that framed our mindsets,” he says. “From that mindset, we decolonized our work here.”

Walking a new path together

Social work has a long, controversial history among Indigenous people. Scholar Raven Sinclair, in Wicihitowin: Aboriginal Social Work in Canada, the first Canadian social work book published in 2009 by First Nations, Inuit and Métis authors, writes Indigenous people in Canada have equated the profession with the theft of children, destruction of families and the deliberate oppression of Indigenous communities. “Social workers were tasked to accompany Indian agents onto reserves to remove children to residential schools and later, in the 1960s and 1970s, to apprehend children deemed to be in need of protection,” Sinclair wrote.

Indigenous children are still vastly overrepresented in government care. The 2021 census shows Indigenous children made up 53.8 per cent of all children in foster care in Canada. In BC, 67.5 per cent of children in government care are Indigenous, while Indigenous people only make up 5.9 per cent of the overall population. Research shows Indigenous people who were in government care as children experience poorer health and socioeconomic outcomes later in life than those who were never in care.

But at UVic, Yoachim met Indigenous social work faculty members who have worked tirelessly to change a colonial system, focusing on strengthening the well-being of Indigenous children, families and communities.

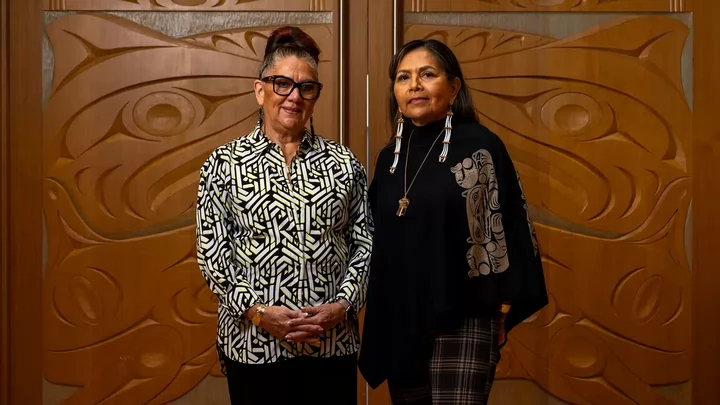

Faculty members Qwul’sih’yah’maht, Robina Thomas, BSW ’93, MSW ’00, PhD ’11 and Kundoqk, Jacquie Green, BSW ’98, MPA ’00, PhD ’13, and now retired Métis scholar Sohki Aski Esquao Jeannine Carrière, along with Indigenous faculty members past and present, have transformed how social work is taught at UVic.

As Canada marks 10 years since the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action, the School of Social Work has been quietly leading the way in Indigenization and decolonization efforts for more than two decades, training about 300 graduates in its Indigenous specializations. Their alumni have gone on to become leaders in Indigenous organizations and communities, helping put child welfare back into the hands of Indigenous communities.

This work has rippled across UVic, influencing the creation of First Peoples House, UVic’s Indigenous Plan and the Indigenous recognition ceremonies for Indigenous graduates during convocation.

Shaking things up

Social Work professor Mehmoona Moosa-Mitha remembers the day Green walked off the stage at convocation. Thomas turned to Moosa-Mitha and said, “We need to hire Jacquie in the School of Social Work.”

Thomas, a member of Lyackson First Nation with Snuy’ney’muxw and Sto:lo ancestry, had joined UVic in 1998 as a visiting lecturer before being appointed to a tenure-track position. Moosa-Mitha says Thomas shook things up, bringing in residential school Survivors to talk about their experiences and challenging Eurocentric notions of social work. When Green was hired in 1999, she and Thomas became a team. “They were a force to be reckoned with,” Moosa-Mitha says. “Now they could have each other.”

Social work’s first Indigenous faculty Elizabeth Hall, Kathy Absolon, Gord Bruyere and Gale Cyr, and Indigenous instructors including Margaret Kovach had laid the groundwork for Indigenization and decolonization efforts in the school. Years earlier, UVic had started delivering decentralized community-based Indigenous social work programs to Indigenous territories across BC. Green’s mother, a band social worker, had earned a BSW through such a program and then an MSW. “Jacquie and I were able to step on the shoulders of giants who had started to create a path that allowed us to create the specialization,” Thomas says.

Green, from the Haisla Nation, and of Tsimshian/Kemano ancestry, had done the groundwork to create an Indigenous specialization during her master’s degree. She had completed a mainstream BSW at UVic and felt it hadn’t prepared her for the work she wanted to do. So, for her final master’s project, Green travelled across BC, interviewing more than 50 people in Indigenous communities about changes they’d like to see to make social work education better. Thomas and Green continued to consult with local First Nations communities, bringing their needs and perspectives to the Indigenous specialization as they wrote the courses.

Weaving together worldviews

Both of Green’s parents had attended residential school. She knew the Indigenous specializations had to strengthen the identities of Indigenous students, many of whom were reconnecting with their culture. Students needed a safe place to deal with the racism they continued to experience, as well as work through intergenerational trauma from residential schools and the child-welfare system. “We needed to include healing components as part of our education. We needed to relearn our ceremonies and cultural practices,” Green says.

The pair wrote courses that balanced academic rigour, writing and theory with ceremonial and land-based teachings and being in community. “It was a matter of weaving the two worldviews together,” Green says. The duo are now both campus leaders. Thomas is UVic’s acting president and vice-chancellor, while Green is the executive director of the Office of Indigenous Academic and Community Engagement (IACE).

In the early 2000s, the School of Social Work launched the BSW Indigenous specialization to prepare students for leadership roles as helpers and healers in Indigenous communities and organizations. The school also introduced an Indigenous child-welfare specialization, with an emphasis on the wellbeing of Indigenous children, families and communities. These undergraduate specializations were open to people with Indigenous ancestry and taught solely by Indigenous faculty members. “We were one of the first in Canada to do this,” Green says. “We’re the only program where registration for the Indigenous specialization is only for Indigenous students.”

Almost 15 years before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission called for social workers to be properly educated and trained about the history and impacts of residential schools, the School of Social Work introduced a core third-year course, Introduction to Indigenous Perspectives on Social Work Practice, for all social-work students.

“We did everything we could to ensure more Indigenous children did not get harmed,” Thomas says.

Better supports for Métis students

The Indigenous specializations have continued to evolve, responding to the needs of students and Indigenous communities. When Sohki Aski Esquao Jeannine Carrière joined UVic in 2005, she brought a Métis lens to her work. Originally from the Red River area of Manitoba and a Sixties Scoop Survivor, Carrière advocated for better supports for Métis students and a stronger presence in social work’s curriculum. Cathy Richardson joined the School of Social Work a couple of years later. The two Métis scholars worked together, eventually publishing Calling Our Families Home in 2017, the first book written in Canada that described the Métis child-welfare experience. “To bring a Métis presence to a university on the coast was not an easy thing. That’s probably of what I’m most proud of,” Carrière says. In 2009, the School of Social Work launched a master-level Indigenous specialization. Carrière, Thomas and Green had created the program off the side of their desks.

They formed an Indigenous circle to advise the development of their Indigenous specializations. The school hired more Indigenous faculty members and sessional instructors, as well as academic advisors. They developed supports for Indigenous students that extended faculty wide. In 2013, the three women founded the Indigenous Child Wellbeing Research Network.

Carrière says the whole university began paying more attention to matters related to Métis students and faculty. “I started noticing more Métis faculty, Métis gatherings, Métis Elders at First Peoples House,” she says. “The landscape started to change and be a safer place for Métis people.”

When Cowichan Tribes asked that the master’s program be taught in Duncan in 2009, Thomas says Indigenous faculty members “literally took our curriculum and drove to Duncan” during that first year. “There is a history of us responding to community in that way,” Thomas says.

Last year, Cowichan Tribes established its Child and Family Services Authority: Stsi’elh stuhw’ew’t-hw tun Smun’eem, becoming the second First Nation in BC to have assumed full responsibility for its child-welfare services. “Our students have gone on and done amazing work,” Thomas says. “We learn from the students [and] they learn from us.”

Grounded in community

Thomas earned a PhD in Indigenous Governance from UVic. Her dissertation focused on Indigenous women and leadership, so it seems natural that Thomas would one day move into leadership roles. In 2017, Thomas became the inaugural director and executive director of IACE, which serves as a hub for cultural, academic and community connections. There, she helped create UVic’s first Indigenous plan.

Green, too, accomplished her own firsts. In 2013, she became the first Indigenous person to become director of the School of Social Work and the first Indigenous person in Canada to head a mainstream post-secondary social-work program.

A year earlier, Green became the first person to defend a PhD at her Haisla community, near Kitimat. One hundred people watched her defend her dissertation, an auto-ethnography that drew on Haisla traditions, culture and language, and more than 500 people gathered to celebrate in the feast hall.

Bringing an anti-oppressive approach to her leadership in social work, Green introduced consensus decision-making. She decolonized the school’s admissions process to ensure Indigenous, Black and other racialized students received fair consideration beyond their GPA when applying. The influence of these two women continued to extend beyond social work when in 2021, Thomas was named UVic’s first Vice President Indigenous, and Green was appointed to IACE in 2022.

Current School of Social Work Director Gayle Ployer says Indigenous faculty members have been instrumental in shaping the work around Indigenization and decolonization at UVic.

“I don’t think it’s the school. It’s the Indigenous community and Indigenous faculty that have been at our school,” Ployer says.

When Thomas and Green realized that many of their Indigenous students were first-generation university graduates, they organized special recognition ceremonies to celebrate the occasion. The ceremony would eventually be taken on by IACE in the First Peoples House, becoming a regular part of UVic’s convocation, and a highlight for Indigenous graduates.

The origin of the First Peoples House, a home away from home for Indigenous students, came from Indigenous faculty members and students within the former Faculty of Human and Social Development, which included the School of Social Work.

Ployer has felt, in many ways, like a witness.

“My experience is, they have a dream, then they do it,” she says. “The rest of us follow.”

Commitment to transformation

Like their mentors, social-work graduates are carrying forward the responsibility to lead with vision, compassion and a commitment to transformation.

Thomas had encouraged Yoachim to apply for the role at Kw’umut Lelum. The organization has continued to grow under his leadership. Last year, Kw’umut Lelum opened Orca Lelum Youth Wellness Centre, BC’s first culturally appropriate detox and treatment services for Indigenous youth aged 12 to 19. “I am so proud of how we have Indigenized our practices,” Yoachim says. “Through all the good work we’ve done here, we haven’t gotten away from our Indigenous Coast Salish values.”

The School of Social Work has been talking about Indigenous children, community and family wellness for a long time. Now as part of the Faculty of Health, Indigenous social-work faculty members Cheryl Aro, Billie Allan, Gwendolyn Gosek, Amanda LaVallee and Jenny Morgan are carrying forward that legacy, turning their focus to health and wellness.

“My hope is that the School of Social Work can play a central role in sharing their expertise in the field of health broadly and in the work we’ve done focusing on children’s well-being,” says Thomas.

—Stephanie Harrington, MFA ’17

Alumna spotlight: Answering the ancestors’ call

In the Kwak’wala language, Sasamans means “our children.” Lori Bull, a member of the ‘Namgis First Nation and executive director of Sasamans Society in northern Vancouver Island, understands the importance of keeping Indigenous children in their community.

A Sixties Scoop Survivor, Bull was taken as an infant from her mother, a residential school Survivor, and placed into foster care with her brother in 1971, where she spent the first four years of her life.

After being adopted by parents from the ‘Namgis First Nation, Bull and her brother grew up in Alert Bay, where her biological mother, who is originally from the Dzawada’enuxw First Nation in Kingcome Inlet, went to residential school.

“We were within our community and culture and within the language that was able to shape who we are now,” Bull says. “Even though we weren’t with our own biological family, we were still within our community.”

When Bull graduated high school, she bristled at the idea of going to university. But her experience as a child in care drew her to social work. “It was like a calling,” she says.

In 2009, Bull graduated from the University of Victoria with a Bachelor of Social Work, specializing in Indigenous child welfare. Then, in 2016, Bull returned to UVic for her master’s degree in the School of Social Work’s Indigenous specialization.

She vowed to never work in government child welfare. Bull now oversees Sasamans Society in Campbell River, a community-driven organization that provides services to strengthen families and children in a culturally appropriate way.

“I credit everything I am today to the Indigenous specialization at UVic,” Bull says. “That program really helped me to develop as an Indigenous woman doing this work in community.”

This article appears in the UVic Torch alumni magazine.

For more Torch stories, go to the UVic Torch alumni magazine page.