Land loved

October 04, 2023

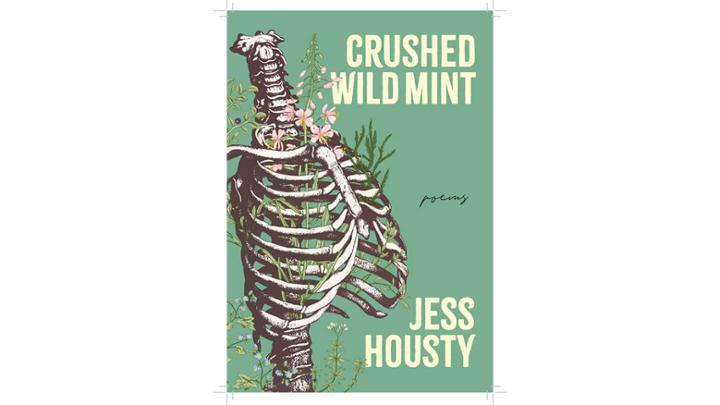

UVic Humanities grad Jess Housty brings love of their rainforest home and Heiltsuk culture to a debut poetry collection, Crushed Wild Mint, that opens the heart and awakens the senses.

Like many writers, Jess Housty has a messy desk, covered in “six coffee cups and 500 Post-It notes.” But Housty’s preferred writing space is actually a little open boat, where the poet travels around their Bella Bella home in the grizzly-rich heart of the Great Bear Rainforest on the Central Coast.

"There are so many beautiful estuaries and meadows close to the village, just to go out and be in nature and write and revise and move those drafts along out in the wilderness. I often don’t bring them back to my desk and type them up until they are close to their final form.”

The poems start as “fun little explosions,” which reveal themselves “sometimes at inconvenient times,” Housty, who uses they/them pronouns, acknowledges. Those explosions are now a full-fledged poetry collection, Crushed Wild Mint, published by Nightwood Editions.

Community and connection

Housty ('Cúagilákv), who is of mixed settler and Heiltsuk (Haíɫzaqv) ancestry, never learned to drive a car. Their world is on the water and in the woods. They grew up home-schooled in their small community, before leaving the rainforest to attend high school in Victoria.

“It’s such a beautiful place to be. I am surrounded by wilderness all of the time,” says Housty, speaking from Bella Bella. “I commute by boat far more often than I’m ever in a car. The immediacy of nature and culture is so different here. So, it was really beautiful to grow up immersed in that and really strange to leave all that behind when I was in Victoria.”

Leaving a community of 1,400 to attend a high school with 1,400 students was jarring. “It was so strange to me, to go from an experience of living that is so intimate and personal and community-oriented to a life in Victoria that was so much more individualistic.”

Housty chats between phone calls and meetings for their work as executive director of the Qqs Society—named after the Heiltsuk word for eyes. Having served as an elected tribal councillor while in their 20s, Housty has a long history of activism and serving their community. The focus with Qqs is on youth and culture, including outdoor camps in the remote wilderness. Housty is excited to have young people in the community read the collection.

“I spent a lot of time thinking what it would be like to have an audience outside my community and people I didn’t know reading the book... but the idea of young people in my community holding that book in their hands and hopefully knowing that they could do that too, seeing that they’re moved by it, that they’re excited by it—that’s by far the most meaningful part of this experience for me.”

The author has two children, sons aged six and eight—and they are inspiration. “I’ve worked really hard to raise my kids in the way that I was raised. To have them outside a lot. To have them connected closely to their food systems. Out on the land, on the water harvesting foods and medicines, to have them grow up deeply connected to their culture to feel how close their ancestors are here in our homelands. I think the most important thing I want to give them is continuity.”

In one of the collection’s poems, “Breath,” Housty draws from a delightful conversation with one of their sons.

“One of my children believes

that all wind originates

in the bellies of wolves,

that storms come from their howling.”

“I think everybody thinks their kids are brilliant,” Housty laughs, remembering the comment. “He asked me one day ‘where does the wind come from?’ and before I could answer, that was his hypothesis that he shared with me. It struck me as such a beautiful and interesting way to view the world.”

There is restlessness and howling and pain woven into the poems—but there is also the comfort of family, medicine, healing, grace, and agency. In the same poem, the narrator assures, “It’s your right to be in pain, my love” and later, “It’s also your right to heal.”

The land is a teacher

The book is ripe with beautiful and interesting ways to view the world. The term “land love” is mentioned on the jacket copy for Crushed Wild Mint. While it could be argued that Housty has every reason to be cynical, the poems are anything but. The healing power of the land has become a deep truth for Housty.

“I spent a lot of time, particularly in my 20s, fighting pipelines, working on big campaigns focused on land protection and fighting extractive industry and trying to address the harms of capitalism and colonization on my people, my community, and territory. I spent a lot of time angry,” Housty recalls.

“It's really easy to be motivated by anger in doing that kind of work. But what came through really clearly to me was that it burned me out. Anger was not a sustainable route to the work I wanted to do in my life... so it has been a really deliberate choice and one we make over and over again every day to let love be the thing that is showing up brightest and to be motivated by love for my people, my ancestors, my culture, my land—and for that to be what's leading me.”

Housty admits to being nervous about others reading their most intimate thoughts. But Housty has not shied away from challenges in the past—including fighting the Northern Gateway pipeline, an experience that was depleting and left emotional scars. Housty hopes their sons do not have to fight as hard.

“If there's something I wish could change, it's that there would no longer be threats to our place-based culture and identity. I hope they won’t have to spend as much time as I have spent in my life fighting to protect our homelands. I hope we come to a place where we can simply thrive here without constantly fighting extractive industry to keep the place that we love safe.”

Housty has written poems since childhood, but stresses that their sense of purpose and identity comes from serving community and territory. “I would have nothing to write about without the richness that brings into my life.”

Earning an English degree at UVic in 2009 honed their reading skills. “When I think about my time in the English department, I know that learning how to be a good reader was a really huge part of learning how to be a good writer. At least for me, I had to be a reader before I could be a writer. That’s one thing that I’m really grateful for, to be able to sit really deeply with other people's texts and stories and poems.”

Housty is an educator as well, co-teaching a Geography field school with UVic professor and graduate Chris Darimont. The duo credits the land as working alongside them.

"We always tell the students: the land is a co-teacher in our course. The land is a teacher showing up for the students... the stories that come from connection to land are a really deep and valid and important part of their learning process. That’s true in the field course, that’s true in my writing, that’s true in how I experience the world around me. There is a shared narrative that includes me and includes the land, and it gives a lot of shape and purpose to my life and is something that is constantly motivating really deep learning for me.”

Darimont and Housty have worked together for years—and he has helped to organize an on-campus reading of Crushed Wild Mint at First Peoples House. “Jess Housty’s words transport us into an ancient rainforest geography where the veil between the natural and supernatural vanishes,” observes Darimont.

Housty, who describes themselves as quiet and introverted, is not drawn to the public eye, even though they are not a stranger to it. “Times in my life when I’ve been in the spotlight it’s been on behalf of a campaign or an issue or advocating for someone or something else. I’m finding it's a really strange experience to have the focus be on not just me but my intimate, personal thoughts, which are now suddenly accessible to virtually anybody,” they reflect. “It's been an interesting process sitting with that and emotionally releasing my attachment to my words, and accepting that they’re going to land differently for different people and that's not something I can control.”

But the work and effort comes back to love. “I’m so in love with my land and so in love with my culture and just feel such a deep sense of joy and dignity and connectedness that comes from that. That’s what I want to uplift. That’s what I want to be front and centre in my life and in my work.”

—Jenny Manzer, BA ’97

Housty will be on campus at Ceremonial Hall, First Peoples House Monday, Oct. 16 from 2:30 to 4 p.m. for a reading and Q&A about Crushed Wild Mint. Everyone welcome.