Puzzles from the Holocaust

- Philip Cox

A long search for lost family stories

The details were sparse, but the crux of the story was clear: Lea Perla Blumenfeld had been shot and killed by Nazis at a forced labour camp during the Holocaust—and one of her sons was forced to bury her.

Almost 80 years later, this was the story told to Lea Perla’s great granddaughter, Lisa Abram, the communications officer for UVic Libraries, by an older cousin during the week of mourning following Abram’s father’s death in late 2021.

As a third-generation Jewish Romanian-Canadian, Abram had been led by her parents to believe that no one on either side of her family was killed in the Holocaust. How had she never heard of this before, she wondered in a state of disbelief. And who was the son in the story?

Were it not for the fact that Abram was working with one of the university’s leading Holocaust Studies experts at the time, this may have been the end of the story, rather than the beginning. As it turned out, she was exactly the right person to solve these puzzles from the Holocaust, working in exactly the right place.

I’ve always been curious. I liked to do puzzles as a kid. My dad would often hide one of the pieces from me—maybe to keep me curious and not give up when there was a piece missing. I think that gave me the interest and skill set to put all the pieces of this puzzle together.”

—Lisa Abram

Early efforts

Since childhood, Abram had wondered vaguely about her great-grandmother on her father’s side, whose painted portrait had hung on her grandmother’s apartment wall for decades. “It was the only image my grandmother had of her mother when she immigrated from Romania,” Abram recalls.

The bits and pieces of her father’s family history that she had picked up in her youth were enough to satisfy her then, but as an adult coming of age just prior to the advent of the internet, she gradually realized that her understanding of her ancestry was partial at best.

Casual inquiries into her paternal grandmother’s place of birth in Mihaileni, Romania, had turned up precious little—the small northeastern town was presumably too small for inclusion in most printed maps—and unimpressive answers from friends of Romanian descent and the occasional Romanian expats that she encountered had only dampened her curiosity at the time.

A turning point in her search almost came around 2016 when Abram’s nephew asked about their family history, which prompted her to seek out information about the ancestral hometown online. The most promising result was an old memoir titled My Dear Shtetl Mihaileni that had been published just before the turn of the millennium.

Clearly a labour of love for a time gone by, the first-person narration walked its readers through the main street of the small shtetl (Yiddish for “town”), recalling in surprising detail its businesses and the families that operated them while describing the buildings, forests and rivers that surrounded them.

When a search for what Abram thought was her great-grandmother's given name, Leah Pearl, returned no results, she tried without luck her grandmother's maiden name: Schwartz. Wondering if the names of her grandmother's brothers might work instead, she unsuccessfully searched for Sam and then Nathan Chitaru, then forwarded the memoir’s link to her sister with a note that, though interesting, the document unfortunately contained nothing about their family. All told, it was five years before another clue emerged.

A new mourning

Throughout the week after Abram’s father had died in August 2021, Abram spent countless hours at her parents’ home sitting with visitors, sharing memories with family and friends, and sifting through the boxes of her father’s files that had been moved from his office and now filled the family’s house.

Alvin Abram was a serial entrepreneur, art dealer and author who wrote a couple of award-winning books and self-published some 20 more. Among his works were stories of Holocaust survivors that he began writing after a friend’s mother shared her own experiences with him.

I wasn’t interested in the Holocaust at that time, but what happened at that meeting changed my life forever,” Alvin Abram wrote in one of his unpublished stories. “I expected to hear a story of pain and death; about loss and anger. I was wrong. I listened as Ibi read to me love letters she had sent to her husband in a labour camp which were returned to her by mail, unopened, when the war ended. He had died and she had been unaware. When she read me those letters, I then realized that the Holocaust was not about numbers but about people and each one had a story that needed to be told.”

It is no small irony that a member of Alvin Abram’s own family had a story from the Holocaust that needed to be told, and that it was during shiva—the week of mourning following his death—that his daughter, Lisa, would learn about it.

Among the visitors who came to pay their respects to Lisa Abram's father was her older cousin, Bryon, who then told Lisa about their great-grandmother's murder in the Holocaust. Bryon said that he had learned this story directly from their uncle Nathan—the son of Lea Perla and brother of Lisa's grandmother, Annie—in the 1950s when he was still a child.

However unlikely it seemed to Abram that her father had never heard this before, she had seen an emailed reply to her sister’s inquiries about their family history in which he explicitly stated that he knew very little of his maternal grandparents. And, surely, as one writing about Holocaust survivors, this story would have surfaced, had he known.

“It’s unfortunate that my dad had to pass away for all this information to come out. That’s something he would have wanted to know,” Abram reflects. “But I don’t think I would have wondered what had happened to my great-grandmother otherwise. I had moved on from that; then my dad’s death brought me back to that question.”

Among the notes, drafts, manuscripts, receipts and invoices that Alvin Abram left behind was a series of documents from the Ontario Jewish Archives that indicated he had donated some personal files including, among other documents, a small trove of old family photos.

Eager to learn more about her family’s hidden history, Abram booked a visit and was invited by its archivists to identify the people in the photos for their records. Finding that there were significant gaps in her knowledge, she called for help from a close cousin of her father’s, Sheila, and the two began filling in names as best they could.

Among the photos, several in particular stood out: a series showing Abram’s grandmother Annie standing with a man and a woman outside an airport, which Sheila identified as Lea Perla’s youngest son, Moshe Itzak, and his wife Seindla in Israel. This was a complete shock to Abram. She had grown up with her grandmother and heard stories about two brothers—Sam in Canada and Nathan in Israel, both of whom she had met. But here was a third, who also lived in Israel, about whom Lisa had never heard. Sheila recalled visiting Moshe Itzak and Seindla while her parents were there in 1970, she said, and remembered that he had a daughter and a son whom she had only met that once.

So many new questions emerged. Why had Abram never heard of this younger brother? Was this the missing son of Lea Perla who had been forced to bury her in the forced labour camp? Abram was plagued by such questions for weeks at a stretch as she spent all her free evenings and weekends searching for more pieces of this puzzle.

Expert advice

By sheer coincidence, around this time, Abram began working with internationally renowned Holocaust historian Charlotte Schallié on a campaign for UVic Libraries that promoted research and teaching partnerships between librarians and faculty members happening on campus.

Schallié, who is also the current chair of the Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies, was at the time in mid-production of But I Live: Three Stories of Child Survivors of the Holocaust, a deeply compelling and now multiple-award winning collection of graphic novels co-created by Holocaust survivors and accomplished graphic artists that was published by University of Toronto Press.

In the moments between photo shoots, Abram shared with Schallié this incredible hidden family history that she had learned and all the dead-ends she’d stumbled upon along the way.

I was very excited about Lisa’s research and immediately wanted to support it. I warned her, though, that unearthing such violent histories risks intergenerational trauma for the descendants of survivors. Breaking a wall of silence within one’s family can also prompt unexpected feelings and expressions of anger and resentment, which can be difficult to navigate. My advice was for her to have a community of care in place and to consider seeking professional counseling support so that family members could feel comfortable discussing difficult emotions.”

—Holocaust historian Charlotte Schallié

Along with this advice, Schallié offered to connect Abram with a network of people who were formally or informally connected to UVic’s Holocaust Studies program and who might be able to help with her search. Among them were one Holocaust survivor and one child of a survivor, both of Romanian descent: David Schaffer, whose story is one of three shared in the But I Live collection; and Micha Menczer, who participated in a unique online exhibit that tasked undergraduate and graduate students with the re-telling of a local survivor’s story as part of a Holocaust and Memory Studies course run by associate professor Helga Thorson for the Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies that spring.

Schallié also connected Abram with another of her colleagues who specializes in Jewish genealogy, Daniel Teichman, and recommended a number of resources that might aid Abram’s research, including the publicly accessible websites for institutional repositories like the Arolsen Archives, housed at the International Centre on Nazi Persecution in Bad Arolsen, Germany; the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC; and Yad Vashem in Jerusalem.

Back home that evening, Abram began searching her grandmother’s family name online once more, this time filled with hope that the archives suggested by Schallié would lead to new results. “Schwartz,” she searched, without success; then “Leah Pearl.”

“Chitaru” she typed, still optimistic, but was once again left frustrated and without a clear way forward.

Changing names

Never one to leave a puzzle unfinished, Abram began reaching out to other members of her family for clues about the various names used by her ancestors. A breakthrough came from a second cousin, Gail, who reached out to a cousin of hers who lived in Israel and whom Abram did not know.

From information provided by this second cousin, Abram learned several details about Moshe Itzak Chitaru, including that fact that he had three children who had a number of children of their own, all living in Israel. More significantly, she learned that the Chitaru family name had multiple variations—Kitaro, Kataru, Chitaro—that, over the decades, had been orally transmitted and recorded in different ways by different people.

Returning to her search once more, Abram began plugging every conceivable variation into the US Holocaust Memorial Museum database, “and there it was! My great-grandmother’s name—spelled Lea Perla Chitraru, with an added ‘r’!” Abram exclaims. “It was like a punch to the gut! I also realized that I had been searching for what must have been her Canadian first name all along!”

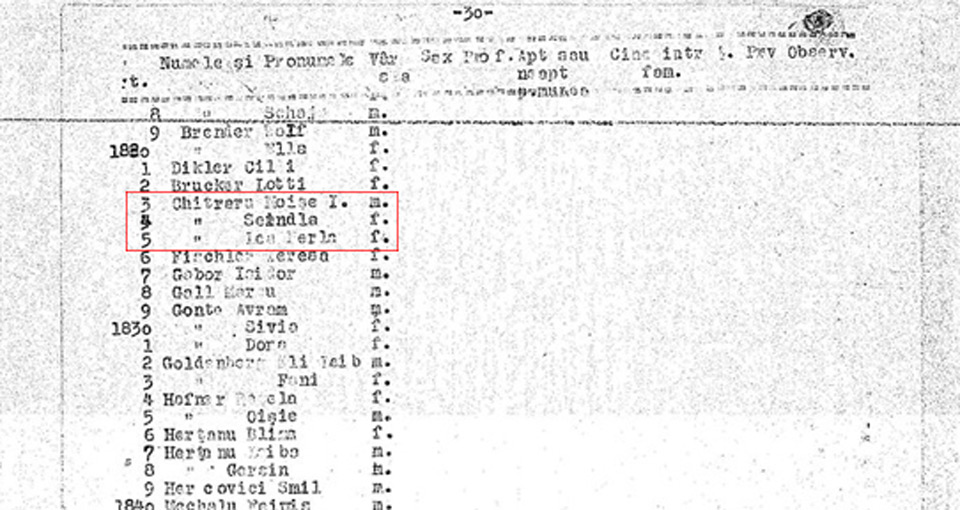

Among the archive's files was a “list of Jews recruited for forced labour in Moghilev, [Ukraine], Dec. 1, 1943” that contained Lea Perla’s name and, just above it, those of her son, Moshe Itzak and his wife Seindla—evidence at last that promised to help set the facts straight.

“I had only heard the story from my cousin Bryon, so it was easy to wonder … how could it be true? How could I not have known?” Abram says with bewilderment in her eyes. “But there it was. When I saw their names… it was just an ‘oh my God’ moment. Not like jubilation, though. It was more like horror.”

From Mihaileni to Moghilev

In a moment of inspiration, Abram returned to the memoir of Mihaileni that she’d found years earlier and, much to her surprise, there they were too. Among the “friends and neighbors” described were “Moise Itzic [sic], Perla’s son” along with rich, detailed stories of the family in better days, including a now-comical scandal involving Perla’s brother, Shimshon “the American” (as they called him) who had just returned home after two decades in Canada and slapped a police officer for what he felt was impropriety on the officer’s behalf.

These anecdotes connected Abram to her past in a way that she’d never felt before, as they began to outline a family history that she could never have imagined. Smudging these lines, though, was a pervasive sense of horror that she could not shake. With half her imagination replaying those scenes in Mihaileni, she could not help but wonder how her family had ended up in Moghilev.

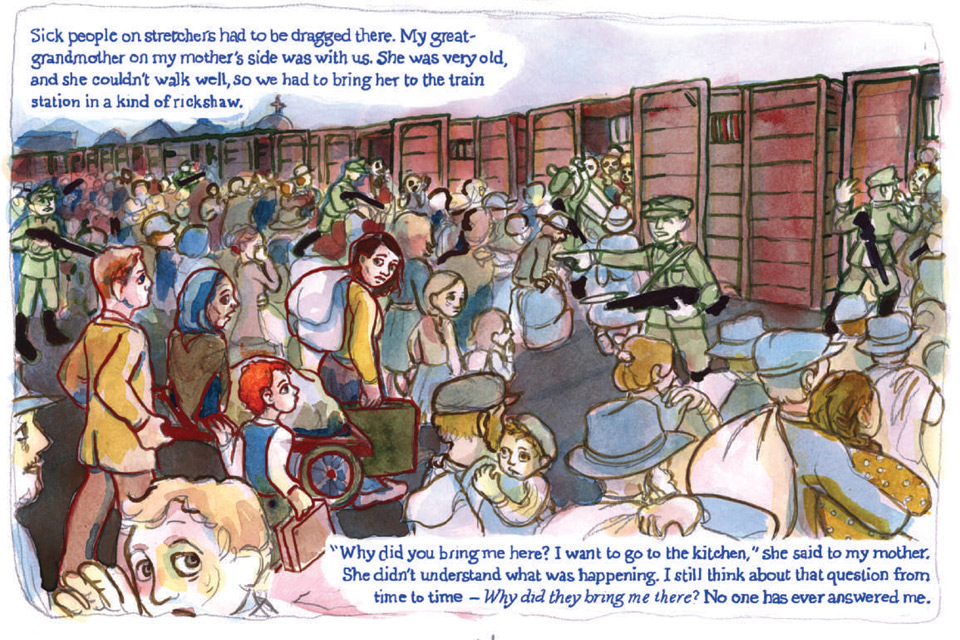

Imagine her shock, then, when she began reading an advanced copy of Schallié’s edited collection, But I Live, and found fragments of exactly that story told in the first-person by David Schaffer, whose contact information Schallié had provided to Abram some weeks earlier.

It’s an amazing connection that Charlotte [Schallié] made for me. David was from Romania and had been in the same forced labour camp in Ukraine where my family was. His story ends with him moving to Mihaileni, where my family is from. I’d been searching for that village for years, and there it was on the map tracing his journey. For the first time ever in my entire life, there it was in print. I knew I had to talk to him. It was all coming together!”

—Lisa Abram

Romania in the Holocaust

Ahead of her conversation with Schaffer, Abram was able to learn a certain amount about her great-grandmother’s shtetl and the history of Romania through historical context included in the But I Live collection, research conducted with help from the staff at Yad Vashem, and several conversations with Micha Menczer, whose father also lived in Mihaileni after surviving the Holocaust.

In short, Mihaileni had been a majority-Jewish Romanian township known for commerce and trade for 200 years before the political and territorial upheavals across Europe in the early 20th century caught up with the local populace.

Antisemitism had been on the rise in Romania for decades—perhaps prompting Abram’s grandmother to migrate to Canada with three of her siblings in the 1920s; another unsolved puzzle for another day—before the nation-state fell into the orbit of Nazi Germany in late 1940, when right-wing political movements found popular support through anti-Jewish platforms. Once the former monarch, King Carol II, was deposed, a coalition of military officers led by General Ion Atonescu came to power and then formally joined Romania to Germany’s Axis alliance shortly after.

Increasingly severe restrictions and anti-Jewish laws were quickly implemented, and violence against Jewish groups, organizations and individuals quickly became the norm. This increased Antonescu’s favour with Hitler and set the stage for state-sanctioned massacres of the Romanian Jewish population. Survivors of these pogroms were herded into transit camps, then deported to the recently-annexed Transnistria region, where they were often murdered, worked to death, or left to die from neglect and malnutrition in ghettos and camps like the one where Abram’s family had been in Moghilev.

A historical essay in But I Live indicates that the total number of Jewish people killed in Romania during the Second World War has been estimated to be between 280,000 and 380,000—the second-highest number for a European country outside of Germany.

These facts suggest that, although Abram’s cousin Bryon believed it was the Nazis who murdered her great-grandmother, it is far more likely that the perpetrators were actually Romanian, as David Schaffer’s story corroborates.

Kristin Semmens, an associate professor in UVic’s Department of History whose forthcoming book, Under the Swastika in Nazi Germany launches on February 9, notes that although this distinction is important, it does not change the basic tenets of Abram’s story.

What happened in Romania really complicates the common narrative that the Nazis were the only perpetrators in the Holocaust. The actions of the Romanian perpetrators took place under conditions created by the Nazis and interacted with, exacerbated and propelled the Nazis’ so-called ‘final solution.’ These actions were not just side-effects of the Holocaust; they were a part of the Holocaust.”

—UVic historian Kristin Semmens

Among those killed in that terrible synergy was Lea Perla, whose forced transit through Romania and Romanian-controlled areas is recorded in a series of legers found by Abram in the US Holocaust Memorial Museum and Yad Vashem archives. Where one document from 1943 suggests that she, her son and his wife were transferred from Moghilev to another camp in the nearby city of Tulcin, another document from that same year suggests that only the son and wife arrived. Had all three perished, their absence from that leger might never have been noticed at all.

Picking up the pieces

When Abram finally spoke with David Schaffer over Zoom last spring, she could never have anticipated how transformative the conversation would be for her.

He was able to solve in short order one puzzle that had plagued Abram’s search for months: several immigration documents had registered her grandmother’s family name as Schwartz, and her grandmother’s brothers’ as Chitaru. However, their father—Lea Perla’s husband—was registered under the family name Mahalu on his death certificate, while their mother—Lea Perla—was registered on Abram’s grandmother Annie’s Canadian marriage licence under an entirely different family name that ultimately proved to be her true, Jewish given name: Blumenfeld!

“There is an old Jewish joke I wish share with you,” David Schaffer told Abram. “A Jew with the Romanian-sounding family name Petrescu changes his family name to Georgescu. ‘Why did you change your name again?’ his friend asks, to which he replies ‘there are many official forms that ask for my previous name, which I did not like because I had to write that Petrescu’s former name was Blumental. Now I can write that Georgescu’s former name was Petrescu!’ Perhaps this joke will help you to understand the conditions and fear people had, and the need to hide the Jewish identity in certain places at certain times.”

Along with such invaluable insights, Schaffer also recounted his time in Mihaileni and retraced for Abram his path across Romania during the Holocaust, which aligned at many points with the route on which she now knows her family to have been taken, enabling her to visualize their harrowing journey by drawing from his experience.

Talking with David Schaffer was like touching the past. From his story I was able to imagine the transportation of my great-grandmother, Moshe and Seindla to the forced labour camp. In a lot of ways, his story is their story, because almost all the Jews were taken on the same trains; they were all marched across these same vast distances. I told David, ‘I wish I could see through your eyes. I wish I could see what you saw when you were there, terrible as it was.’ Reading and hearing his story was the closest I was ever going to get to understanding what life in the Holocaust was like for my family!”

—Lisa Abram

Songs from the past

A few weeks later, on May 1, 2022, Abram attended an event at the Jewish Cemetery of Victoria for Yom HaShoah, an international day for the commemoration of the six million Jews murdered in the Holocaust. She sat in the audience with around 100 or so others, listening to touching speeches and family stories of some who survived and others who perished.

A woman in glasses with graying hair, a red sweater and purple scarf sat down before the microphone with a guitar on her lap and solemnly sang Ich Shtei unter a Bokserboym—a rendition of a poem about the trees in Israel, written by a Jewish Belarusian poet, Zyame Telesin, who had served as a front-line war correspondent for the Soviet Union throughout the Second World War.

“I stand beneath a carob tree,” the woman sang in Yiddish, though Abram could not have understood the words. “I got there, but not easily, not easily….”

Within Abram stirred old memories of her grandmother’s voice and the soft echoes of the Yiddish songs she played that comprised the soundtrack of Abram’s childhood.

“I stand beneath a fig tree…. and all around is green and free, is green and free….”

Months of seemingly endless research and frustration had culminated in this moment. Decades of her family’s history collapsed into this elegy.

“I lie beneath an almond tree… it appeared a dream to me, a dream to me….”

Abram approached the singer to tell her how beautiful was the song she sang, and how much it had meant to her, but the words just would not come.

“A carob tree, a fig tree, an almond tree,” the song continued playing through her mind. “I stop my tears, not easily, not easily….”

And there, upon the sallow field of mossy paths and aging headstones, before this woman she did not know, Lisa Abram broke down and wept.

Connections for the future

Today, with the support of staff at the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 in Halifax, Lisa Abram's family project spans 52 pages of text, a plethora of photos, news articles and archived documents about family members she had never known existed, and a family tree with several branches and more than 100 names newly added.

"Within these files are a rich array of records about Moshe Itzak and several generations of his descendants in Israel that were unearthed by Daniel Teichman, the genealogist recommended by Schallié, which reveal a complex story about Abram’s great uncle that her father would very likely have wanted to tell."

Sometimes she daydreams about going back to her childhood home, walking up to her father, and handing him her files. “Here dad,” she wants to say. “Here’s this massive file on our family’s history that I’ve built. I want to share with you this story that you would have been writing about yourself.”

Among the relatives with whom Abram shared her findings, none among her father’s living cousins and their children had known about their connection to the Holocaust and the intergenerational disconnections it had caused within their family. Many were stunned by how much of this history had been withheld from them, but not all were interested in learning more.

"One newly found cousin in Israel in particular—a descendant of Moshe Itzak, with whom I connected through Teichman—asked why I’m so interested in these terrible things that happened in the past. We’re in the future now, he said. I told him that I need to understand my past to understand my family’s history and who I am. Connecting with him was the future for me," Abram shares."Besides that, I just want to honour the story of my great-grandmother, Lea Perla Blumenfeld. I just want to keep her name alive.”

—

Stories like these are important in sharing human experiences and building connection, but they may surface feelings connected to intergenerational trauma and post-traumatic stress. If you or someone you know would like further support in processing trauma, here are some suggested resources:

- Jewish Family Services Community Care Line: 604-558-5719

- Foundry: 1-833-308-6379

- Vancouver Island Crisis Line: 1-888-494-3888

- UVic Employee and family assistance program: 1-844-880-9142

- SupportConnect(for UVic students)

- UVic Counselling Services (for UVic students)

Photos

In this story

Keywords: Holocaust, history, racism, international, German and Slavic Studies

People: Lisa Abram, Charlotte Schallie, Kristin Semmens, Helga Thorson

Publication: The Ring