Expert Q&A on producing survivor-centred Holocaust graphic novels

Four Holocaust survivors and three graphic artists have worked tirelessly to co-create a series of three autobiographical graphic novels about one of the darkest times in human history. Today, a multi-year global effort culminates in a beautifully rendered, one-of-a-kind collection that frames the enduring lessons of the Holocaust.

But I Live: Three Stories of Child Survivors of the Holocaust is edited by Holocaust historian Charlotte Schallié, chair of the University of Victoria’s Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies and project lead of the UVic-based Narrative Art and Visual Storytelling in Holocaust and Human Rights Education. Here, Schallié speaks to the role of the visual arts in Holocaust education, the importance of survivor-centred storytelling practices and trauma-informed approaches to ethical testimony collection, as well as the urgency of preserving survivor experiences.

The UVic-based project, first announced in January 2020, involves an international team of researchers, students and institutional partners spanning three continents, supported by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and focused on the stories of Emmie Arbel (Israel), Nico and Rolf Kamp (Holland), and David Schaffer (Canada) through the unique, hand-rendered styles of graphic artists Barbara Yelin (Germany), Gilad Seliktar (Israel) and Miriam Libicki (Canada).

But I Live was released today by New Jewish Press, a division of University of Toronto Press (one of North America’s largest university presses).

May is Canadian Jewish Heritage Month.

Q. What can these graphic novels teach us about the Holocaust that we didn’t know before?

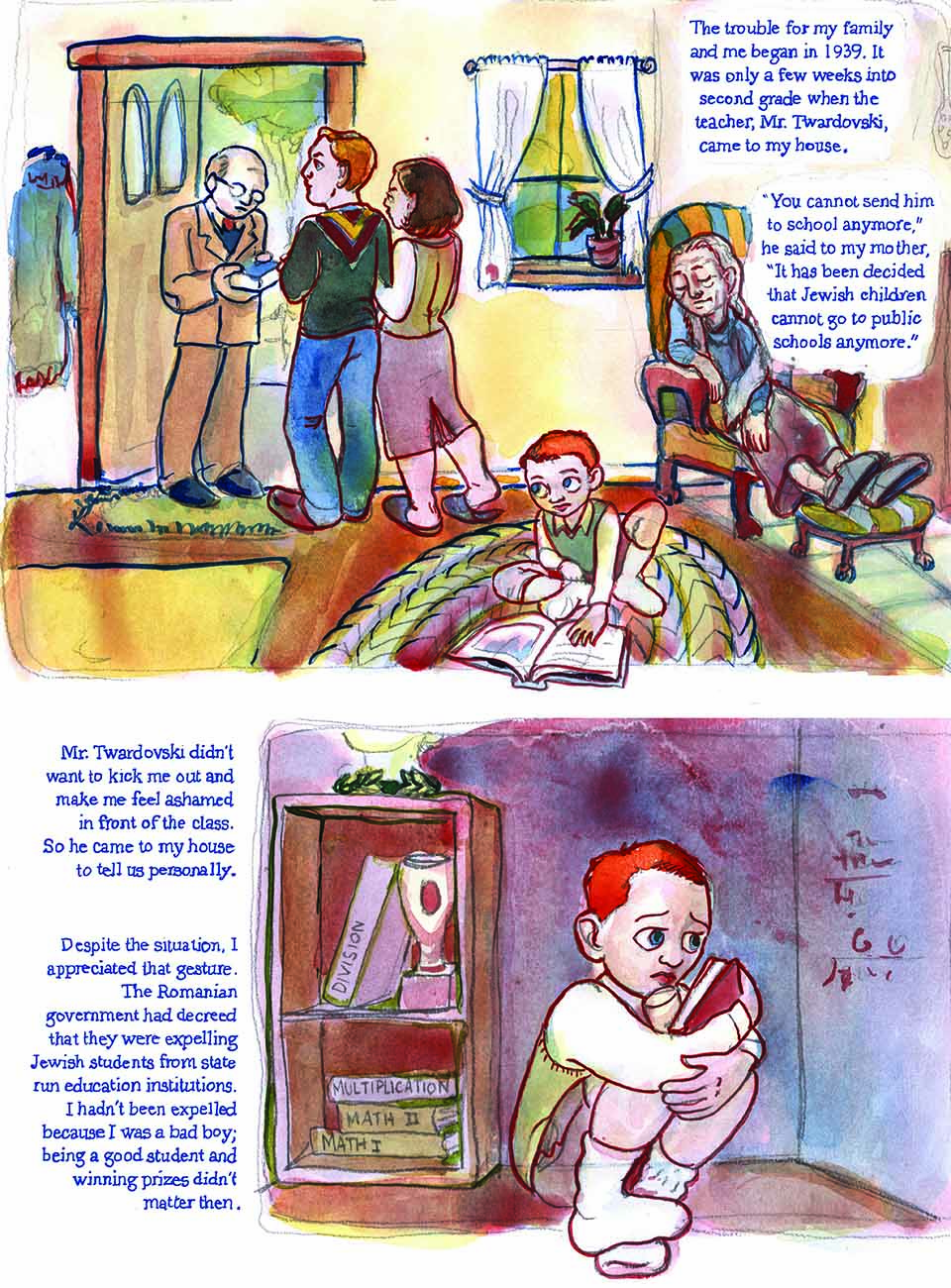

A. Many people in North America have learned about the history of the Holocaust through survivor stories that are repeated in popular culture, which largely focus on survival in the concentration camps or experiences of hiding in Nazi-occupied territory. The three stories in But I Live complicate these mainstream narratives by exploring complex topics such as the burden of memory, the need to testify, the ripple effects of trauma and the impact of the Holocaust on descendants of survivors, for example. As historical documents, they are also important for centering the survivors’ experiences and enabling them to tell their own stories.

The enormity of the crimes committed during the Holocaust is well documented, yet the majority of visual records that we have were largely produced by the Nazis and their collaborators. These are important historical sources, but a sole focus on documentation produced by perpetrators ignores the value of survivors as living knowledge keepers.

Grounding the history of the Holocaust in the knowledge and living memory of those who survived helps show its relevance and urgency for understanding the gross human rights violations of the current moment.

—UVic humanities scholar Charlotte Schallié, Holocaust historian, project lead and editor of But I Live

Q. Why is it important for Holocaust survivors to be able to tell their own stories?

A. We have extensive documentation of mass atrocities created by the perpetrators of the Holocaust that meticulously captures acts of extreme violation, degradation and dehumanization. The aim of these documents was to erase any individual traces of a victim’s identity and experience. A survivor-centred approach to gathering testimony about the Holocaust honours the integrity and humanity of the person’s lived experience while respecting their right to tell their own story.

Time is also a factor, as we are quickly approaching what is described as the “post-witness” era. The majority of Holocaust survivors alive today were children at the time, born in the years between 1935 and 1938, which means they are in their mid 80s. At best, we might have another 10 years to learn from these knowledge keepers, human rights activists and educators. If we don’t engage them in our research now, their expertise and experience will soon be lost.

Finally, I believe that we have a moral obligation and duty to collect and preserve survivor testimonies. Each voice that was marked to be silenced by the perpetrators of these atrocities matters greatly and needs to be heard and acknowledged.

Q. You’ve described But I Live as the product of a collaboration between historians, artists and Holocaust survivors. Can you explain the process behind this unique collaboration?

A. Building on the foundational research of oral historian Henry Greenspan and other survivor-centred projects, we developed a community-engaged, collaborative and trauma-informed approach that focused on ethical testimony collection practices and arts-based co-creation.

Eliciting experiences and memories of extreme human suffering from the survivors necessitated a research process and practice that privileged their safety by minimizing the risk of re-traumatization, managing potential triggers and providing sustained support for all participating project partners.

This approach ensured that we—the stewards of survivor memories—honoured what we felt was our obligation and duty to amplify the voices of the Holocaust survivors.

We were extremely fortunate to work with three wonderful artists who treated the four survivors and their life stories with compassion, care tenderness, and love.

Q. What gap do these graphic novels fill as resources for Holocaust education?

A. In Canada, where teaching and learning about the Holocaust is not mandated in high schools, we hope that our visual storytelling work will appeal to youths and young adult readers, and elicit within them a deep sense of empathy that leads them to think critically about the historical past and present.

Holocaust survivor stories that are presented as heroic narratives, where the storyline progresses from dark to light—or, from a site of danger to one of safety—place a heavy burden and responsibility on survivors whose life stories and memories are unlikely to conform to that model, and simplifies the reality of their lived experiences. But I Live holds space for fragmented memories, difficult emotions and the afterlife of trauma. In doing so, it complicates mainstream tropes, clichés and iconographic imagery that is sometimes misappropriated or exploited in popular culture.

These graphic novels also encourage the reader to experience stillness, silence and contemplation. Readers need to slow down their reading and pay close attention to panel compositions, rhythm and timing in storytelling, shifting colour palettes and changes in narrative voices and perspectives. The artwork in But I Live cannot be passively or hastily consumed. It requires a deep intellectual engagement from the reader on multiple levels, spurring self-reflection and a willingness to critically engage with, and to think and feel through, the life stories and memories of our four Holocaust survivors.

-- 30 --

A media kit containing high-resolution photos from this project is available on Dropbox.

Photos

Media contacts

Charlotte Schallié (Germanic and Slavic Studies) at schallie@uvic.ca

Philip Cox (Humanities Communications) at 250-857-1061 or humscomm@uvic.ca

Tara Sharpe (University Communications + Marketing) at 250-721-6248 or tksharpe@uvic.ca