Indigenous people managed shellfish and sea otters for millennia

- Anne MacLaurin

New collaborative research shows that for millennia, Indigenous people managed their relationship with shellfish and sea otters to safeguard their access to shellfish—a resource which remains important today for food, social, and ceremonial uses.

A historical patchwork of sea otters

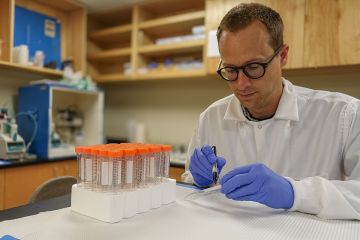

Iain McKechnie, UVic coastal archaeologist and corresponding author on the study led by SFU graduate student Erin Slade, explains that the team found much bigger mussels in archaeological sites than in areas where sea otters have recovered today. This indicates that ancient Indigenous communities excluded this shellfish predator from areas near human settlements, where people valued similar intertidal foods.

Traditional foodways need protection

“Indigenous communities coexisted with sea otters but prevented them from impacting locally important shellfisheries,” says McKechnie. “This study highlights a much larger issue in conservation and restoration where targets, policies and laws often don’t recognize the extent of Indigenous settlement history and the long-term management of coastal place.”

Kii’iljuus, also known as Barbara Wilson, a Haida Matriarch and elected representative of the Council of the Haida Nation, said the study is significant both scientifically and culturally. After years of seeing her culture’s traditional management practices dismissed or ignored by policymakers, she said the results were validating.

Our people have talked about this for hundreds of years. It’s important because it shows how our ancestors managed the oceans and all the critters—both on land and in the water—and how conservation was built into that management.

—Barbara Wilson, Haida Matriarch and elected representative of the Council of the Haida Nation

New opportunities

Wahmeesh (Ken Watts), elected Chief Councillor of Tseshaht First Nation which supported archaeological research in Barkley Sound, sees opportunity stemming from this research. “People are stepping up and trying to figure out solutions. Don’t underestimate the power of people. We have the ability to create change. It’s just a matter of doing it and doing it together.”

The research is a collaboration between several First Nations including Tseshaht, Heiltusk and Wuikinuxv as well as UVic’s Department of Anthropology, SFU’s School of Resources and Environmental Mangement, the Hakai Institute & the Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre. The study included data from the the UVic archaeology field school as part of the Kakmakimilh Archaeology project co-directed by Tseshaht archaeologist Denis St. Claire.

Funding provided by Natural Sciences Engineering Research Council, Canada Foundation for Innovation, Hakai Institute and the Pew Fellows Program.

Find out more

- Research highlights

- Coastal Voices website

- "Archaeological and Contemporary Evidence Indicates Low Sea Otter Prevalence on the Pacific Northwest Coast During the Late Holocene" (2021) Erin Slade, Iain McKechnie & Anne K. Salomon Ecosystems

Photos

In this story

Keywords: research, Indigenous, sustainability, environmental studies

People: Iain McKechnie