Print matters: between sisters

- Jenny Manzer

Aggie and Mudgy: The Journey of Two Kaska Dena Children, by UVic anthropology alumna Wendy Proverbs, traces the 1,600-kilometre voyage of sisters forced from their remote village to Lejac Residential School.

Aggie and Mudgy are the names two sisters chose for themselves because they rejected the names assigned to them when they were baptized into the Catholic Church. Their Indigenous names, those given to them by their Kaska Dena community in a remote BC village, were lost over their years in residential school.

“They didn’t like the names the priests gave them, so they renamed themselves. To the day they died, they still called each other Aggie and Mudgy. That’s quite powerful, I think. They never accepted the priest’s names,” says author Wendy Proverbs.

The two sisters are the main characters in Proverbs’ novel for preteens, Aggie and Mudgy: The Journey of Two Kaska Dena Children, published by Heritage House last fall. The book follows the Indigenous girls, aged eight and six, as they travel from their home village of Daylu to Lejac Residential School in central BC. They are accompanied by an unkind priest, Father Allard, a sinister man who wears long black robes. The novel is complemented by illustrations from Alyssa Koski.

Their trip covers a stunning 1,600 kilometres, including a border crossing and transport by riverboat, mail truck, paddle wheeler, steamship and train. Even more astonishing is the fact that this part of the story is factual—based on the true story of Proverbs’ biological mother, Mudgy, and her aunt, Aggie.

Proverbs was adopted as an infant during the era known as the Sixties Scoop, when many Indigenous children were removed from their families and placed in the child-welfare system. She was fortunate to be adopted into a loving family, and grew up in Prince George. As an adult, she began to learn more about her birth family. While working on her Masters at UVic in 2012, she received a copy of her aunt’s memoir, which included details about that long journey. Proverbs shakes her head at the fact that the priest was also able to cross over into Alaska and back with the girls—apparently without being questioned or delayed.

In deciding to write about the story, Proverbs set out to honour the women and make sure they weren’t forgotten. “This was an opportunity to give Aggie and Mudgy a voice, and they also represent many other children across our country that went through many similar situations and were never heard.”

Proverbs created a fictional present-day story as scaffolding around the painful true details. The contemporary story begins with eight-year-old Maddy finding an old photograph of two young girls and asking who they are. Loving grandmother, Nan, shares the tale with Maddy over several days as they chat, drink tea, bake pies and go on field trips. The warmth and care of the contemporary family adds a gentle touch to the narrative for middle-school readers.

“Children maybe need a little cushion to… comprehend the harsh reality of what happened to these children,” observes Proverbs. Along the way, readers learn historical and geographical facts about the many places—a kind of love letter to the land.

Proverbs intentionally chose the middle-grade audience after seeing a gap in books available about reconciliation. She is also hoping to reach young, open minds.

I don’t believe there’s enough literature aimed at that particular age group to get their minds thinking about Indigenous life and Canada and how we arrived at today—and how they relate and see Indigenous people. I think that was my original goal.”

—Author Wendy Proverbs

While she had her aunt’s memoir as source material (a work written for immediate family), Proverbs also visited archives and consulted church records, although many from residential schools have not been made public. While researching, she found a note about her uncle, who, sadly, appeared to arrive at Lejac after his sisters. Proverbs discovered he was sent home to Daylu after contracting tuberculosis and died there in 1938.

Proverbs made an intentional decision to have the scope of the book only cover the journey, not life at residential school, though the fictional grandmother, Nan, alludes to the difficulties the girls faced there. “It was more about their journey and about the survivors, which are the fictional family of Nan and Maddy—and how they are more or less resilient, carrying on with life, and that sort of gives the whole fullness of the story.”

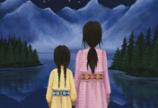

Reading the book, one is struck by Koski's illustrations of the small sisters, side by side, alone together.

“In their hearts, they knew what they were born as, but between the sisters they were just Aggie and Mudgy, and that was a deep bond. It was just the two of them for so long. They were just eight and six when they left their communities,” says Proverbs. “If there was one blessing, it was that they had each other.”

In her own life, Proverbs is married to UVic alumnus Trevor Proverbs, BA ’74, a strong supporter of her writing. They have two children, Geoff and Tracey. Proverbs is now a grandmother herself—much like the character of Nan—and she adores her grandsons. “They are my shining lights. I love being a grandmother.”

Proverbs attended UVic as a mature student, earning a Bachelor of Arts and then a master's, both in anthropology. She says her UVic education made her a better writer.

My degrees provided a comprehensive understanding of human and cultural development, but also a deeper understanding of Indigenous people and their vital contribution to the vibrant society that we exist in now.”

—Author Wendy Proverbs

Proverbs enjoys writing for middle-grade readers, and is currently researching a book on adoption, a topic she believes is under-covered in literature for young people. In March, the book won a Jeanne Clarke Award, given by the Prince George Public Library to recognize outstanding contributions to promoting local and regional history. Proverbs hopes the book will be widely available to schools. “My dream is for this to become a tool within the educational systems for librarians and teachers to pick it up and to share it with their class.”

The real Aggie and Mudgy went on to have difficult adult lives. The two sisters survived residential school, but were not well educated—and economic times were tough. They both worked as domestics. Aggie married and Mudgy had two common-law unions—though the relationships were not good ones. Proverbs’ mother, Mudgy, had 12 children, of which 10 were either put into foster care or placed into adoption. Proverbs has reconnected with several of her biological siblings, and has become particularly close to her birth sister, Barb, who lives in Sechelt—and was able to read an early draft of the book.

As Proverbs writes in the acknowledgments, her birth mother, Mudgy, gave her the gift of siblings. Together, she and Barb travelled to Daylu to see where their biological mother and aunt were born. “The significance of two sisters returning to Daylu close to 85 years after another two sisters were forced to leave was not lost on us. However, that is another story to tell.”

Photos

In this story

Keywords: Indigenous, reconciliation, writing, literature, alumni, anthropology, youth

People: Wendy Proverbs

Publication: The Torch