Stories light a dark history

- Stephanie Harrington

Powerful database reveals extent of Japanese Canadian dispossession

Laura Saimoto never met her grandfather, Kunimatsu Saimoto, or knew the details of his story until she recently accessed his 500-page case file through the University of Victoria’s groundbreaking Landscapes of Injustice project.

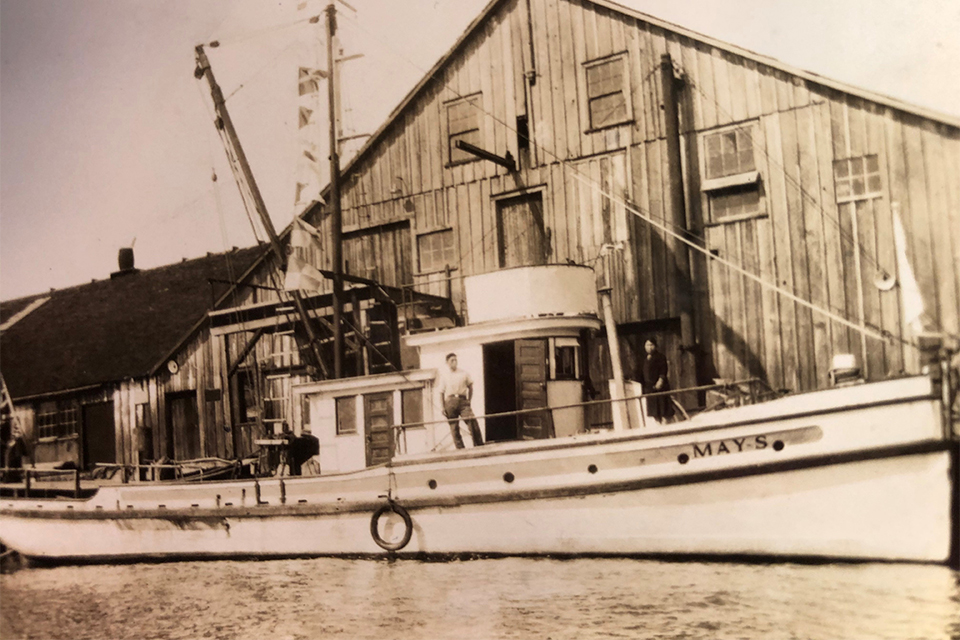

Her grandfather, a Vancouver resident, lost his family home, as well as his possessions and livelihood including four commercial fishing vessels, when the government forcibly interned and dispossessed 22,000 Japanese Canadians during the Second World War.

One family’s story, among thousands – accessible for first time

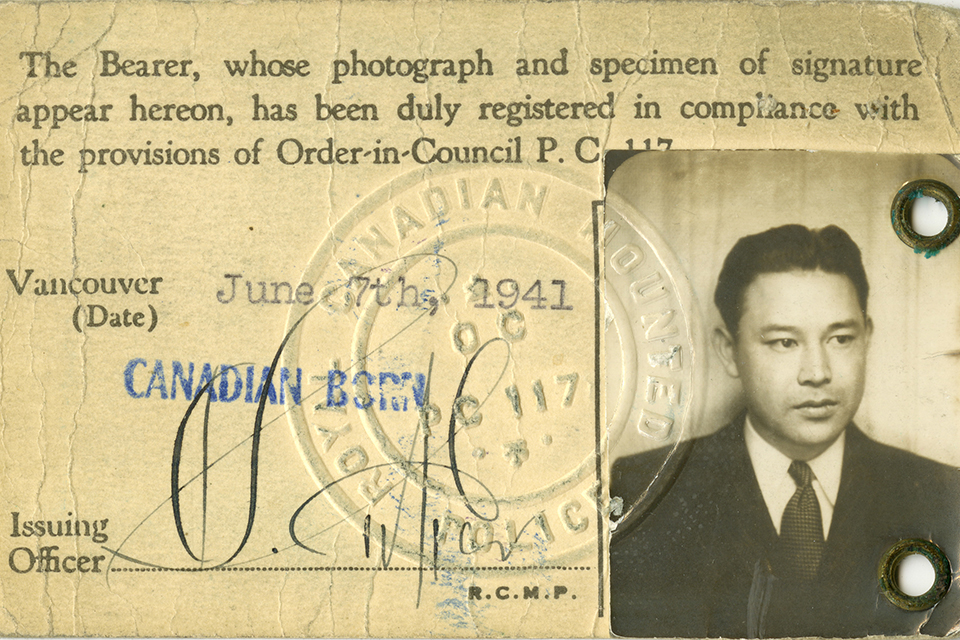

Saimoto wept when she saw his internee number—9609—assigned by the Office of the Custodian, the government authority that oversaw the internment and dispossession of Japanese Canadians from 1942 to 1952.

Now, for the first time, anyone interested in this dark history will be able to easily search tens of thousands of digitized government records, oral histories, land titles, individual case files and personal documents such as photographs and letters that the Landscapes of Injustice team has digitized and organized into a comprehensive online database, revealing the inner workings of this chilling and racist chapter in Canada’s past.

Repercussions of the internment and dispossession

The library contains records detailing more than 15,000 interned Japanese Canadians—at least one file for every Japanese Canadian family affected by the government's dispossession efforts—and includes Custodian Case Files, like the one Saimoto accessed about her grandfather.

The Landscapes of Injustice database will give the public—and many Japanese Canadian families—the power to discover the full extent and repercussions of the internment and dispossession of Japanese Canadians.

Like any government authority that aims to systematically erase a people while telling themselves they were doing nothing wrong, they took meticulous, detailed records. The internment and dispossession of Japanese Canadians was a machine of organization and administration, and everything was documented.

— Laura Saimoto of the Vancouver-Japanese Language School, a partner of the Landscapes of Injustice project

The culmination of a seven-year public history project

Since 2016, the Landscapes of Injustice collective has connected survivors and their descendants with researchers, students, partner organizations and community groups to share once and for all the untold stories of the forced dispossession and displacement of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War.

The digital archive launched this month is the capstone project of this seven-year, multimillion-dollar research and public history project, following the release in 2020 of an edited collection of essays, a narrative-based website, primary and secondary school teaching resources, and a national museum exhibit entitled “Broken Promises.”

This free, open-access database contains over 500,000 pages collected from more than 20 archives and repositories across Canada, the US and the UK, offering researchers and the public an invaluable resource for investigating the records of this historical injustice.

Exactly 79 years ago this month, the Canadian government opened offices to oversee the dispossession of Japanese Canadians. In repudiation of that choice, we are proud to share the hidden details of that process along with the brave responses of Japanese Canadians at the time.

—UVic historian and project director Jordan Stanger-Ross

Background information on this project

Find out more

In this story

Keywords: racism, history, human rights, arts, community, administrative

People: Jordan Stanger-Ross

Publication: The Ring