Day in the Life: Michael Abe

- Tara Sharpe

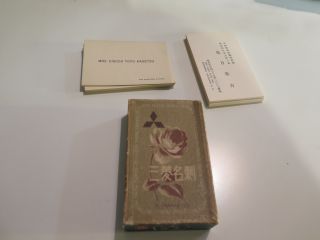

It sits in his home office at arm’s length from his desk.

The wooden side table was built by an uncle of Michael Abe, project manager for Landscapes of Injustice. It is a small but treasured piece of Abe’s family history after being hidden for safekeeping nearly 80 years ago. And it perfectly captures the entire point of the project upon which he works.

Abe is a Nikkei Sansei (third generation Japanese Canadian) and past president of the Victoria Nikkei Cultural Society. He joined the UVic-led, seven-year, multi-partner project shortly after Landscapes was launched in 2014. In a recent interview with CBC radio host Sheryl McKay, Abe described the work as “filling in the blanks of the silence.”

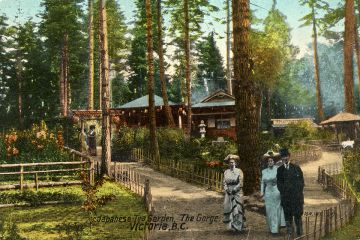

The project focuses on the history and importance of learning about the dispossession of 21,000 Japanese Canadians whose homes, businesses, fishing boats, cars and personal effects were sold without their consent after they were systemically uprooted during the 1940s. The lessons still resonate today with the echoes and ongoing legacies of systemic racism in Canada.

A dream job

Before working at UVic, Abe was employed at Tourism Victoria and Tourism BC/Destination. Having been involved with Japanese Canadian organizations and communities here and in Ontario for years, Abe was elated when he found out about the job opening: “It was a dream come true, one of those ‘dream jobs.’”

He manages the administrative aspects of the project, producing newsletters; coordinating meetings and events, as well as the project’s annual institute and sessions and workshops throughout the year; and has also travelled to various locations across North America—from San Francisco and Calgary to Whitehorse and Toronto.

Another key part of his work, at least in the last few years, was the electronic clean-up of case files from the project’s digital archive for Japanese Canadian community members. Abe says it was “a very gratifying process.” In fact, after uncovering family histories much like his own, he received many heartfelt messages from descendants of interned Japanese Canadians.

The files and what they reveal are “crucial to the families who lived these experiences and to their relatives. It’s the most valuable output for this project for our community and it is the part most dear to me,” adds Abe.

For his paternal grandmother, who passed away in 2007 at the age of 99, the historical hardships “didn’t matter. There is a saying in Japanese, shikata ga nai. It means, ‘It can’t be helped.’ For her generation, it was the stoic way to move on. And all that hardship was not for naught because it paved the way to a good life for her children, her grandchildren and great grandchildren. This is why I maintain my ‘Japanese-ness.’”

Abe holds a BSc in biology from McMaster University in Hamilton, where he was born.

He grew up playing hockey and other sports after the family moved to Burlington in suburban southern Ontario.

Abe says he “very much celebrates both my Canadian side and my Japanese heritage. I am just as Canadian as any of the guys in my golf foursome.” So he was “shocked” to learn about his parents’ internment after he interviewed his father for a Grade 8 project. His parents had never told him what had happened during the war.

Till then, I’d been as Canadian as anyone else on my block. I didn’t know I was a visible minority until I was 13 years old.

—Michael Abe, project manager of UVic-led Landscapes of Injustice

His grandmother, with whom he was very close, spoke little English. His grandparents moved to Port Alberni and were interned in Lemon Creek in BC’s Interior. They were from southern Japan, as were his maternal grandparents who were also interned.

He says his grandmother spoke in “a heavy dialect, old archaic Japanese.” He lived with her while at university, then relocated to Japan in the late 1980s to learn more about the culture, language, sumi-e and shuji (brush painting and calligraphy), and martial arts. He laughs when recounting the discovery that his way of speaking the language, as spoken by his grandmother, was antiquated.

While at McMaster, Abe began studying the Yōshinkan style of Aikidō at the Hamilton Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre and he continued his martial arts training while in Kōfu, central Japan where he met his wife.

In 1993, the couple and their young son moved to Victoria where Abe opened and ran an Aikidō dōjō for nearly 15 years.

Both their children are also part of our UVic community: their son is a UVic alumnus and their daughter is currently finishing her undergraduate degree in history.

No longer a burden not to tell

On a recent UVic field trip to Lemon Creek, Abe pointed out to the students a bench dedicated to his family. Abe’s father was still alive when it was installed in 2012. At the unveiling, his father openly spoke about his past: “That was the pinnacle for him, the ‘people are interested in hearing my story’ moment.”

It wasn’t a shameful thing for my father anymore. He no longer had to feel the burden of not telling the story.

—Abe

A third-degree black belt, Abe is “back on the mats” again, teaching Aikidō and also as a novice student of karate. He says there is “a lot to be learned in being a beginner.” He approaches it with shoshin, “a beginner’s mind.”

Aikidō is “very defensive. It takes the momentum and energy of the attacker. You go with it, you ‘neutralize’ it by redirecting out of harm’s way.”

And he reflects that perhaps the project can do the same for one of the darkest chapters in Canadian history.

Find out more

- The journey of the side table (in Abe’s own words)

- Landscapes of Injustice narrative site

- Stories of others touched by dispossession

- More about Broken Promises museum exhibition

- Landscapes of Injustice exhibition trailer (Vimeo)

About the project

In September 2020, the Landscapes project unveiled a new national exhibition as the culmination of six years of its award-winning research.

“Broken Promises,” which runs through April 2021 at the Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre in Burnaby, shares the truth about dispossession in the 1940s through the stories of seven families who lost their homes, personal possessions and livelihoods, along with their civil and human rights, despite government guarantees of protection. Abe takes particular pride in having coordinated the museum launch event, pivoting (due to the global pandemic) to an online broadcast from the original plan for an extravagant and live ceremony. The broadcast has now been viewed more than 4,500 times.

Landscapes is based on the UVic campus at the Centre for Asia-Pacific Initiatives and involves 15 other partners; brings together researchers in two faculties at UVic (humanities and social sciences); and has benefited from the contributions of a research collective consisting of over 100 members from universities, community organizations and museums.

It is supported by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and matching contributions from its institutional partners.

It is one of the largest humanities-based research projects in Canada today.

Videos from opening commemoration

All four videos were produced by One Island Media for the Landscapes of Injustice project

Photos

In this story

Keywords: Landscapes of Injustice, administrative, community, staff, history, Day in the Life

People: Michael Abe

Publication: The Ring