Expert Q&A: Sea otters boost genetic diversity of eelgrass meadows

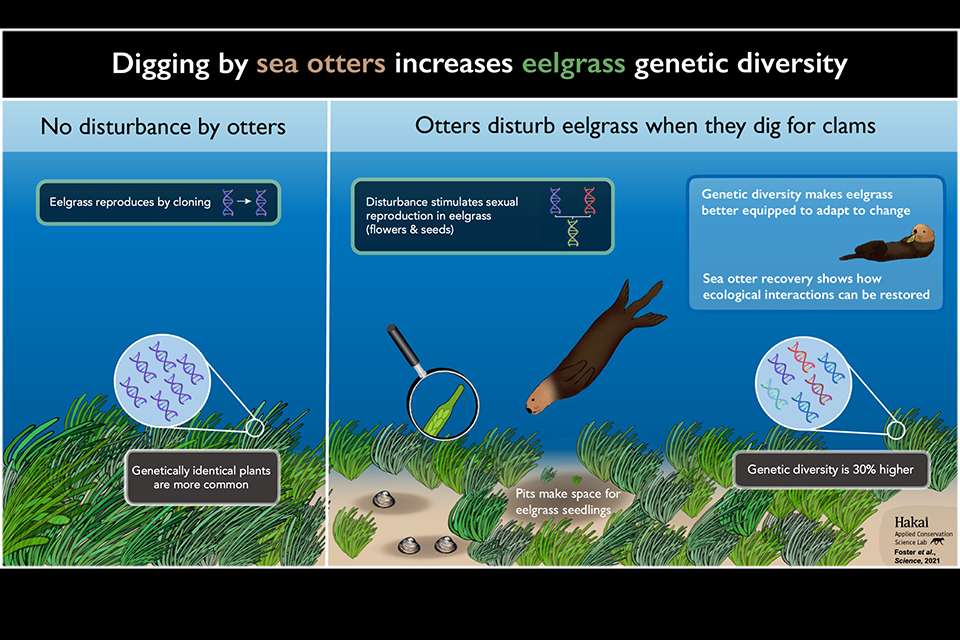

A unique interaction between sea otters and the flowing plant known as eelgrass has researchers looking closer at the co-evolution of the two species. In a paper published today in the journal Science, University of Victoria geography PhD graduate, Erin Foster, explains how the digging activities of sea otters disturbs eelgrass beds, which in turn leads to greater genetic plant diversity.

The research was supported by the Tula Foundation, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada-Vanier and Discovery Grant (supervisor, Chris Darimont). The researchers acknowledge the Ka:’yu:’k’t’h’/Che:k:tles7et’h’, Huu-ay-aht, Haíɫzaqv, and Wuikinuxv Nations in whose territories they worked.

Q. What is the significance of the interaction between sea otters and eelgrass?

A. Eelgrass growing on the ocean bottom inadvertently blocks the sea otter’s access to clams and other food buried below the plants. Sea otter digging disturbs the eelgrass roots and promotes conditions that favor sexual (over asexual) reproduction, enhancing genetic diversity. With asexual reproduction, new plants are genetically identical to the parent, but with sexual reproduction, almost every single seed will be genetically different, since the genes of the two parent plants mix.

In areas where sea otters have been present from 20 to 30 years, eelgrass genetic diversity was up to 30 per cent greater than in areas without sea otters, or in areas where otters had arrived during the past 10 years. The genetic diversity of eelgrass is important to its survival in a rapidly changing environment.

Q. Why is eelgrass important to the environment?

A. The more variety there is in the genetic composition of each individual, the more likely that some individuals will be able to sustain environmental stressors—just by chance. Some individuals, for example, might be very tolerant to heat waves, others to disease, and yet others may tolerate heavy grazing or ocean acidification.

Eelgrass plays a number of important roles in the environment, including preventing shorelines from erosion and providing a habitat for herring and a nursery area for rockfish and salmon. Eelgrass produces oxygen and stores greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide, helping to mitigate climate change. As well, eelgrass is culturally important to Indigenous people as an important source of starch, the roots can be eaten whole, and the seeds can be ground to a flour.

Q. What is your research process?

A. The most important part of my research process has been to think carefully about what others have shared with me over the years. Mentor, friend and co-author, Jane Watson, first had the idea about sea otters enhancing genetic diversity of eelgrass decades ago. Watson thought there must be some mechanism allowing eelgrass beds to thrive despite the digging efforts of the sea otter. We worked together to come up with a study design to evaluate the idea that digging favored sexual production in eelgrass leading to greater genetic diversity.

Q. What do you want people to take away from this research?

A. I hope our discovery will help people think more broadly about the effects that large animals have on ecosystems and understand how the return of a once-absent predator is an important part of future recovery initiatives—for both plants and animals.

A media kit containing an infographic, high-resolution photos and a video is available on Dropbox.

-- 30 --

Photos

Media contacts

Erin Foster (Dept. of Geography) at 250-740-8053 or erin.foster@hakai.org

Anne MacLaurin (Social Sciences Communications) at 250-217-4259 or sosccomm@uvic.ca

Suzanne Ahearne (University Communications + Marketing) at 250-721-6139 or sahearne@uvic.ca

In this story

Keywords: Indigenous, sustainability, administrative, geography, environment, sustainability

People: Erin Foster, Chris Darimont