The human benefits of marine protected areas

- Anne MacLaurin

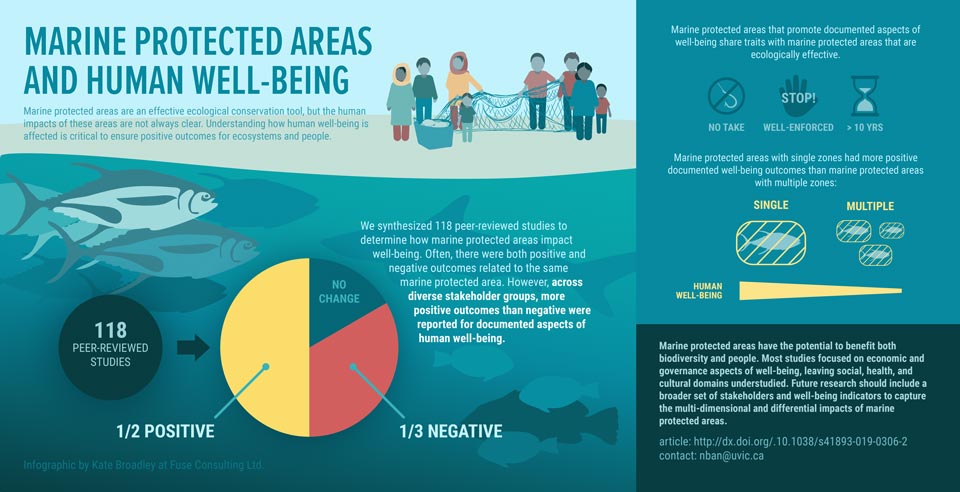

Marine protected areas (MPAs) are well known for protecting biodiversity, but their effects on people who use the oceans are debated. Now a new review—led by University of Victoria marine conservation scientist Natalie Ban and 12 co-authors—illustrates that these protected areas can also support human well-being.

Urgent need for action to protect marine biodiversity and benefit people

This global study found that MPAs that are well-established, no-take and well-enforced had more positive human effects on well-being. This aligns well with findings from ecological studies and highlights that MPAs can benefit both biodiversity and people.

Earlier in May 2019, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services released its first comprehensive scientific report on the global biodiversity crisis, highlighting that one million species are threatened—and urgent action is required.

Currently there are approximately 14,830 MPAs in the world.

Many countries have committed to setting aside 10% of their marine areas as MPAs by 2020 as part of the Convention on Biological Diversity.

Over 70% of the Earth’s surface is ocean. According to recent statistics updated by the World Database of Protected Areas, half of all marine provinces have over 10% of their marine areas protected. More info

Global discussions are currently underway to identify post-2020 targets.

Our study provides the most comprehensive support for the benefits of MPAs for peoples to date, but we still have to ensure that the subset of people who are affected negatively are adequately supported.

—Natalie Ban, School of Environmental Studies, UVic

Global study points to benefits for human well-being

The new study found that more positive (51%) than negative (31%) outcomes of MPAs on human well-being were reported in peer-reviewed studies. The most positive well-being outcomes related to enhanced community involvement (76% positive), increases in fisheries catch per unit effort (73%) and increases in income (65%). The most negative outcomes manifested through increasing costs of fishing (100%, though only 13 instances found in the literature) and conflict (79%).

While there were more positive than negative human well-being outcomes of MPAs, commonly both can be found in the same MPA. For instance, a study in Lyme Bay, England, found that commercial fishers and recreational users had improved experiences since establishment of the MPA, whereas there were also lengthened fishing trips, tension and conflict. Similarly, in an MPA in Vietnam, fisheries catch per unit effort increased (a positive change), whereas the number of fishers decreased (a negative change).

Gaps remain in understanding impacts of MPAs on people

Ban points out that the new study highlights the gaps that remain in our understanding of the effect of MPAs on people. Ban and her colleagues found that most evidence focused on economic and governance aspects of well-being, leaving social, health and cultural domains are understudied.

Similarly, most studies were on the effects on fisheries, providing relatively little insight about human well-being effects of MPAs on, for example, coastal communities or recreation. There was also too little detail in the studies reviewed to understand how different aspects of society are advantaged or disadvantaged by MPAs. For instance, are women affected differently from men? Are some economic or ethnic groups affected differently from others? Future studies should consider these effects, says Ban.

“This is the first global literature review of MPAs that assesses human well-being for all uses, not just fisheries,” explains Ban. “As countries collaborate on the new UN post-2020 biodiversity framework, more attention needs to be spent on examining the benefits and costs of MPAs on all aspects of human well-being, not just economics, and all stakeholders, not just fishers.”

A global review

Ban and her co-authors examined relevant data from 118 peer-reviewed journals. Studies were carried out on all populated continents. The most number of studies were found in Asia (especially the Philippines) and Europe.

The review was carried out by Ban and her 12 co-authors from 11 different institutions in five countries.

This research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council and the Australian Research Council, in addition to other funding.

The paper, “Well-being outcomes of marine protected areas,” was published today in Nature Sustainability.

Photos

In this story

Keywords: oceans, sustainability, biodiversity, fisheries, wildlife

People: Natalie Ban

Publication: The Ring