Classroom under water

- Jennifer Kwan

UVic’s scientific diving program takes students to a whole new world of learning

When second-year biology student Emie Woodburn talks about the University of Victoria’s scientific diving program, she recalls a childhood reflex of pinching her nose under water to avoid flooding her nostrils. It’s a response she gladly unlearned during the program that practices safety protocols over and over again.

Repetition is a hallmark of the scientific diving program, which has given three decades of UVic students the tools and training they need to safely conduct research in the cool depths of the Salish Sea, Saanich Inlet and other waterways. Based on the standards of the Canadian Association of Underwater Sciences, the program is part on-land and open water classroom to train compliance in a highly regulated area, says Andy Mavretic, director of UVic’s Occupational Health, Safety & Environment unit, which oversees the diving program.

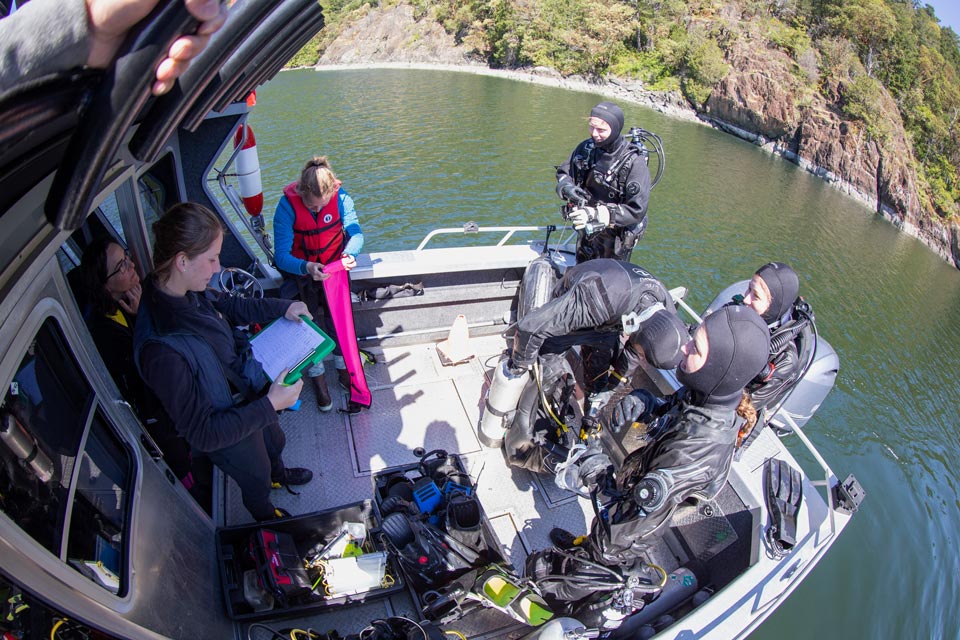

The program, which requires students to develop and lead detailed dive plans that set out dive duration, depth, potential risks and contingencies, provides students with the hands-on learning they need to safely and successfully conduct research under water.

“It’s like a laboratory under water so there are obvious risks,” says Mavretic. “We strive to make the training as real and relevant as possible for the students to help make their research happen.”

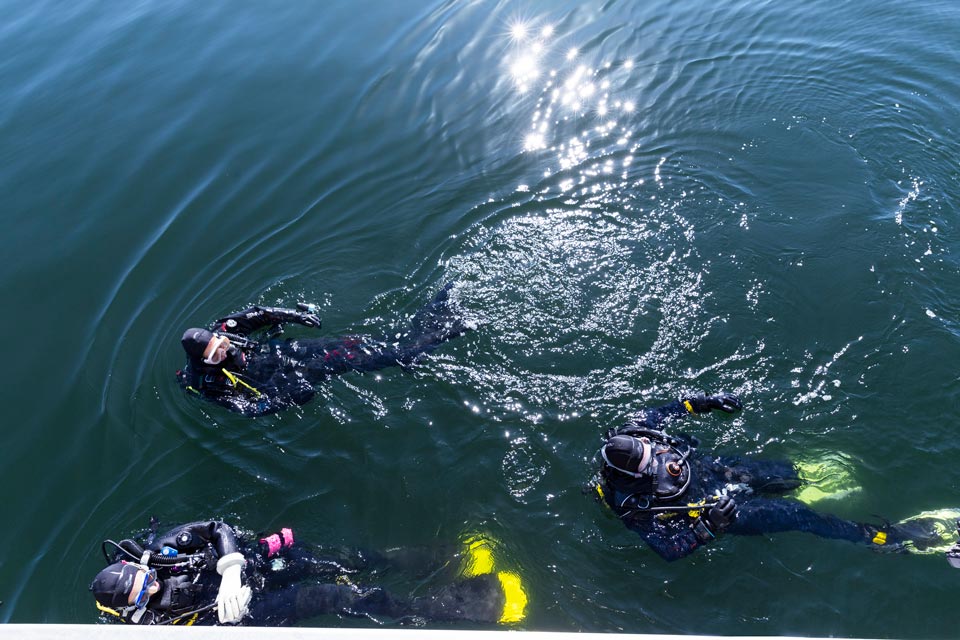

Woodburn’s dive plan focuses on recording biological life—ling cod, crabs, bull kelp—in Ogden Point, southwest of Victoria, and outlines project goal and research techniques to quantify relative abundance of organisms in an area. Beginner divers fixate on equipment, checking air, buoyancy, pace of ascent and descent, as well as search and rescue drills. Dive plans account for emergency procedures including minimizing thermal stress by wearing the right clothes and communicating during crisis.

“The course makes safety tasks second nature. On top of that, you have to think of research tasks,” says Woodburn.

To enroll, students must have past experiences such as recreational diving and first aid. They go through a medical evaluation and they are required to complete about eight hours of course work, as well as pass exams and log a total of 25 dives, which can include pool and onshore diving at Ogden and Henderson points, says Victoria Burdett-Coutts, UVic’s diving safety officer and a seasoned marine consultant.

Boat dive

For Woodburn’s cohort, boat dive training was made possible only through a partnership with the Malahat First Nation, a community of about 350 located on the western shore of Saanich Inlet. After three months of study, students meet at Mill Bay Marina, 42 kilometres northwest of Victoria. Burdett-Coutts is first to arrive and begins unloading gear including snacks, clipboards, first-aid kits, oxygen tanks and thermal clothing.

Students’ level of experience varies, explains Burdett-Coutts, but what’s necessary is physical—the weight of gear is upwards of 70 pounds for each person—and mental discipline. “Watching them gain skills and confidence while working under water is pretty exciting.”

Brian Timmer, a directed studies student in biology working in fish ecologist Francis Juanes’ lab, has a decade of experience as a recreational dive instructor. He saw how the dive program opened doors for other young researchers such as PhD candidate in biology Kieran Cox, who recently notched his 1,000th dive while studying at UVic. Cox has dived in Florida and Belize as a Smithsonian fellow, as well as at Christmas Island with Julia Baum’s lab. “You don’t have to be a scuba diver to work on a computer, but you need people in the water,” says Timmer.

UVic students are able to conduct the offshore dive, thanks to the 28-foot Pride of Malahat Thunder Jet boat owned by the First Nation. Alongside the UVic students, boat captain Dwayne Goldsmith, who is a Malahat Fisheries technician, took part in the course work. This ensures the community has the tools required to be stronger stewards of their territorial waters. Building capacity in the broader community is key, says Tristan Gale, Malahat Nation’s director of Environment and Fisheries. It can expose youth to the world of post-secondary education and inspire them to study environmental science. “It’s these simple ideas and partnerships that can change a person’s life,” he says.

For Woodburn, the course untrained a childhood reflex and also gave her training to do more research under water. She landed a summer job with Victoria-based Cetus Research and Conservation Society and has a new goal — to gain tropical diving experience at the iconic Great Barrier Reef. “It really opened my eyes to a whole new world of research. You can join your passion for diving and study marine biology. It’s the package,” she says.

Photos

In this story

Keywords: oceans, teaching, Indigenous, research

People: Victoria Burdett-Coutts, Dwayne Goldsmith, Andy Mavretic, Brian Timmer, Emie Woodburn

Publication: The Ring