Handling old manuscripts is a hands-on proposition

- John Threlfall

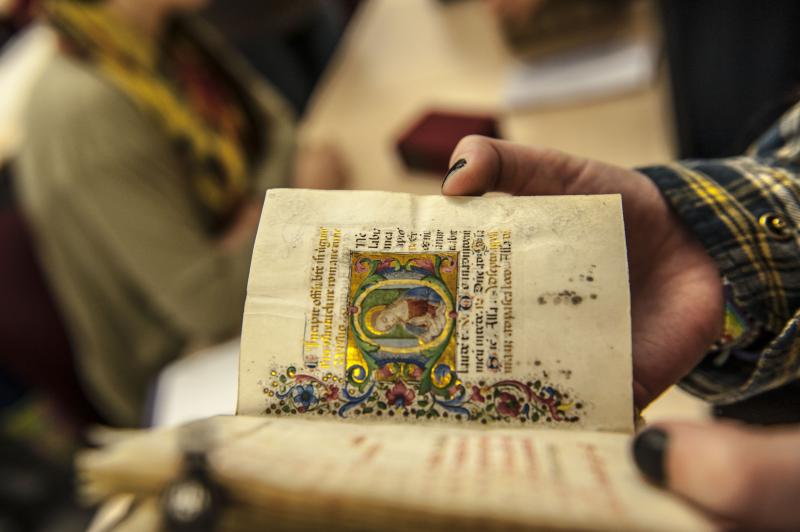

When it comes to handling old manuscripts, there’s no fooling around for UVic researcher Dr. Jamie Kemp—the gloves are definitely off. Despite the lingering meme of white-glove clad researchers delicately handling archival material, Kemp says bare skin is best when it comes to the centuries-old books in UVic Special Collections and University Archives.

“Our rule at UVic, and at most international libraries, is no white gloves,” she explains. “Gloves make you clumsy. You’re far more likely to damage the book by losing that haptic perception—you’re not going to be able to easily turn a page with gloves on, for example—and the cotton can actually wear on the object’s surface, as it’s fairly abrasive compared to your skin. Honestly, gloves cause more problems than they actually solve.”

Kemp, a sessional instructor in UVic's Department of Art History and Visual Studies, well knows of what she speaks. While her doctoral research focused on the cognitive function of images in 15th century encyclopedic manuscripts, her broader research interests include knowledge visualization, image-text relations, cultures of reading and book history. One of her passions in both the Art History and Medieval Studies departments is introducing students to the ancient manuscripts and printed books in Special Collections—absolutely a hands-on proposition.

Don’t feel antiquated if this is breaking news, however: Kemp says the dare-to-bare movement is somewhat recent. “I was originally taught that with parchment, you use bare hands, while with paper, you always use gloves.” (The distinction lies in the object itself—parchment is made out of animal skin, which is very durable, while paper is far more fragile and doesn’t hold up as well over the centuries.) “Now, however, it’s bare hands for everything.”

But don’t think you can go straight from snacking at Biblio Cafe to flipping through a 15th-century tome. Kemp reminds everyone to thoroughly wash their hands before handling any archival object, and ensure your hands are free of oils, lotions and spikey jewelry.

Also, never touch any paintings or gold leaf on the page, and only handle a manuscript by its edges. “Whenever you touch a manuscript, your interaction always leaves an impression—and that becomes part of the story of that book,” she cautions. “It’s just a question of minimizing that story, and preserving the manuscript as best we can.” A good example, says Kemp, is the Allepo Codex—Jerusalem’s 10th-century Hebrew Bible—the edges of which are blacked and crumbling after a thousand years of handling.

Kemp also offers the following cultural caveat: “When we say ‘no white gloves’, we’re primarily talking about books—not every type of cultural artifact,” she explains. “You always want to check with the archivist or whoever’s in charge of the collection.”

Especially in this age of digitalization, Kemp yearns for the intimate sensation that comes with the bare-skin handling of old manuscripts.

“Unlike a painting, you get to interact with a manuscript in the same way as someone in the past,” she explains. “You hold the book in the same way that someone in the 12th century held it."

"It’s our responsibility to preserve that interaction for future generations.”

———

Speaking of medieval manuscripts, the 28th Annual Medieval Workshop, “Burnt at the Stake,” on Jan. 31 and a sequel on Feb. 6 and 7, the free two-day “Witches of the West" symposium, will explore lessons still relevant today about the uncanny connections between witch hunts, mass persecution, modern moral panics, and the flames of medieval and early modern pyres that devoured bodies and books (but not the legacy of ideas and dreams). More info: http://www.uvcs.uvic.ca/medieval-workshop/ and https://mardinalia.wordpress.com/witches-of-the-west/

Photos

In this story

Keywords: art history and visual studies, medieval, special collections, graduate research

People: Jamie Kemp