Ocean of beauty and discovery

- Richard Dal Monte

Verena Tunnicliffe had her first encounter with the ocean when she was seven and held it in the palm of her hand.

She hadn’t yet seen the sea when her mother gave her a box covered with shells, and as she examined their varied shapes and swirls and ridges in their home in landlocked Deep River, ON, they might as well have been fragments of an asteroid, for they represented to her an unknowable world filled with alien species.

“I loved the shapes,” says Tunnicliffe, a UVic biology professor emeritus. “At first, it was just a curiosity item but, gradually, I began to realize … the things were beautiful. And that stayed with me all my life, the beauty of the ocean.

But also that things had a form—you wonder how they get that way. And so that’s what sparks the imagination.”

That imagination fired a passion that saw her build a childhood collection of shells in the shallow space under her bed; dig in the mudflats of the Bay of Fundy—for three summers— while a McMaster University Bachelor of Science student; and study coral reefs off Jamaica.

And it drew her, eventually, to Vancouver Island, from which she explored the deep, dark fjords—730 metres down—off the BC coast in submersibles and began a four-decade career in deep-sea exploration.

For that career, marked by scientific discovery and leadership in ocean research, Tunnicliffe was in December named an officer of the Order of Canada.

‘Pretty crazy endeavours’

Tunnicliffe, who holds an MPhil and PhD from Yale, and conceived and directed development of Ocean Networks Canada’s VENUS Cabled Observatory on the floor of the Salish Sea, says she’s appreciative of receiving Canada’s highest civilian honour but shares the acclaim with colleagues.

“The honour is given to one person but there’s a whole team of people behind you,” Tunnicliffe says.

“It’s just impossible to do the kind of work I do without that team of colleagues and students. But particularly important are the people who have enabled all of that work along the way, which includes the University of Victoria administration, who supported me a lot in some pretty crazy endeavours, because I took some chances.”

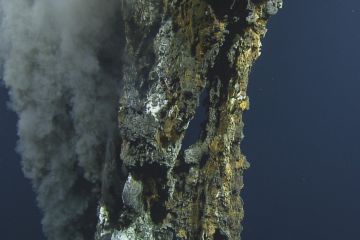

One of those chances was the expedition that would lead to discovery of “hot vents” on the ocean floor and the establishment of Endeavour Hydrothermal Vents Marine Protected Area, a deep-sea habitat and Canada’s first marine protected area.

It’s appropriate, or least consistent, that she credits colleagues for the accomplishments that have marked her career, for the thing she has studied over and over is how different species work together.

“You can gradually build a picture of how the community works and… can begin to analyze how the communities have evolved,” she says.

Different species must work together

Relationships and interdependence among species are a crucial piece of her research work to this day as she looks at how they could be affected by deep-sea mining and resource extraction. She’s currently writing a paper about the western Pacific Ocean, looking at how animals differ from New Zealand to Japan and other locations, and how they’re connected.

But the species she’s most concerned about right now lives above the waves.

“The more we modify environments and take out of our ecosystems, the harder it’s going to be for future generations of humans to meet their needs,” she says, adding, “I feel pretty strongly that we tend to be a species that really has to hit the crisis before it starts doing something.”

The crucial question, then, is: “Can we plan forward better than we usually do as a species?”

Looking back, she is asked about her role as a pioneer for ocean exploration and for female scientists, but again she deflects any suggestions of praise.

“It’s not me as a pioneer, it’s the teams that work with me that are pioneering. I’m good at writing grant proposals”—she laughs—“I’m willing to take a chance. I am not a risk-averse scientist. I have made huge mistakes, I’ve taken gambles that haven’t paid off. But I’m really interested in the big picture of things. My dreams, my fantasies just lead me.”

What’s in a name?

Tunnicliffe has had 10 underwater species named after her. Among them are “a lovely snail” (Admete verenae), “a tiny blob of sponge” (Sphaerotylus verenae) and “a weird, trumpet-shaped limpet” (Cornisepta verenae).

Her favourite, however, is Sericosura verenae, a deep-sea spider that is related to its land-based counterparts; it’s about three centimetres across, she says, and was first collected in an expedition at the Endeavour Hydrothermal Vents Marine Protected Area. “It’s cute, it’s covered with hair, lovely life strategy,” Tunnicliffe says, explaining that the males inseminate multiple females, then carry balls of fertilized eggs attached to their abdomen and incubate them, the females’ work complete.

As with everything for Tunnicliffe, it’s all about teamwork.

Photos

In this story

Keywords: Ocean Networks Canada, research, oceans, biodiversity, climate, research, environment, award, sustainability

People: Verena Tunnicliffe