Enacting Indigenous governance

- Stephanie Harrington

Two years ago, Cheryl Recollet spent several memorable days with other Anishinaabe community members harvesting maple saplings, digging holes, and shaping and tying logs to build a teaching lodge at the Robinson Huron Treaty Gathering.

“We spent four days together, laughing, loving and being,” says Recollet.

A photograph captures the first morning when the group met for a sunrise ceremony: the sky is dark and people huddle in chairs around a fire in the lodge; sapling leaves dangle from the arched maple roof.

For Recollet, a member of Wiikwemkoong Unceded First Nation on Manitoulin Island in Northern Ontario and the director of research at Robinson Huron Waawiindamaagewin (RHW) initiative, the lodge was more than a structure. It was a space to discuss, enact and embody governance.

“This was an exercise in Anishinaabe governance,” she says. “We kept it as a teaching lodge and made that space open and accessible, and a comfortable place for people to learn, as a visual reminder of what Anishinaabe governance looks like.”

First-of-its-kind PhD program

Now, Recollet has taken a step to deepen her knowledge of Anishinaabe governance, to examine how the Robinson Huron Treaty can be meaningfully implemented today to ensure a better future for her people.

She is among the first students in the University of Victoria’s new Indigenous Governance PhD program —a first-of-its-kind interdisciplinary graduate program that allows students to pursue their own research interests while becoming grounded in foundational and cutting-edge scholarship in Indigenous governance. No other PhD-level program in Indigenous governance is offered in Canada.

Recollet, who completed a master of science in Indigenous environmental governance at McGill University after working in environmental management for a decade, is supervised by world-renowned treaty scholars Heidi Kiiwetinepinesiik Stark and Gina Starblanket at UVic’s School of Indigenous Governance.

Her research asks, “How do Anishinaabe implement historical governance practices under the current relationship with the Crown? How did Anishinaabe make decisions prior to contact, and what will Anishinaabe decision-making practices look like in the futures?”

At UVic, Recollet has access to resources that include a collection of historical documents on Anishinaabe governance, as well as networks and supports in place for Indigenous students. Recollet spent her first year in Victoria on campus completing coursework but is now back in her home community working and refining her dissertation topic.

Coming to UVic, being able to be exposed to the vast amount of resources and to dive through those materials is amazing. I'm very grateful for IGOV. I don’t think there would be another place I could do the research I’m doing as meaningfully and fruitfully as I am.”

—Cheryl Recollet

Renegotiating Anishinaabe-Crown relations

The timing for Recollet’s research is ideal—21 Anishinaabe communities that are signatories to the Robinson Huron Treaty are getting closer to resolving a years-long landmark treaty annuities case with the Ontario and Federal governments.

At the centre of the court case was a promise the Crown made when the treaty was signed in 1850 that treaty annuity payments would increase according to the wealth produced by the land. However, while industries such as mining and forestry have generated billions of dollars in profits since that time, payments to the Anishinaabe were capped at $4 per person in 1874 and haven't increased since.

Negotiators are finalizing an out-of-court settlement in which the signatory communities are paid $5 billion, for a total of $10 billion, from both Canada and Ontario for past losses. The Supreme Court of Canada, meanwhile, is due to make a ruling this spring around future annuities negotiations between the parties.

The court case represents a watershed moment— one that promises to reframe the relationship between the Robinson Huron Treaty communities and the Crown, and to have repercussions across Canada.

Taking stock of past, present and future

Through her PhD research and role at the RHW initiative, Recollet will have an opportunity to inform models for treaty governance and treaty implementation going forward. The goal is to develop a collective Anishinaabe decision-making body that pushes for Anishinaabe peoples’ interests and inherent rights, and revitalizes Anishinaabe laws and legal traditions.

"This will be part of my life’s work,” Recollet says. “I’m always looking forward and back, at the historical, the contemporary and future generations.”

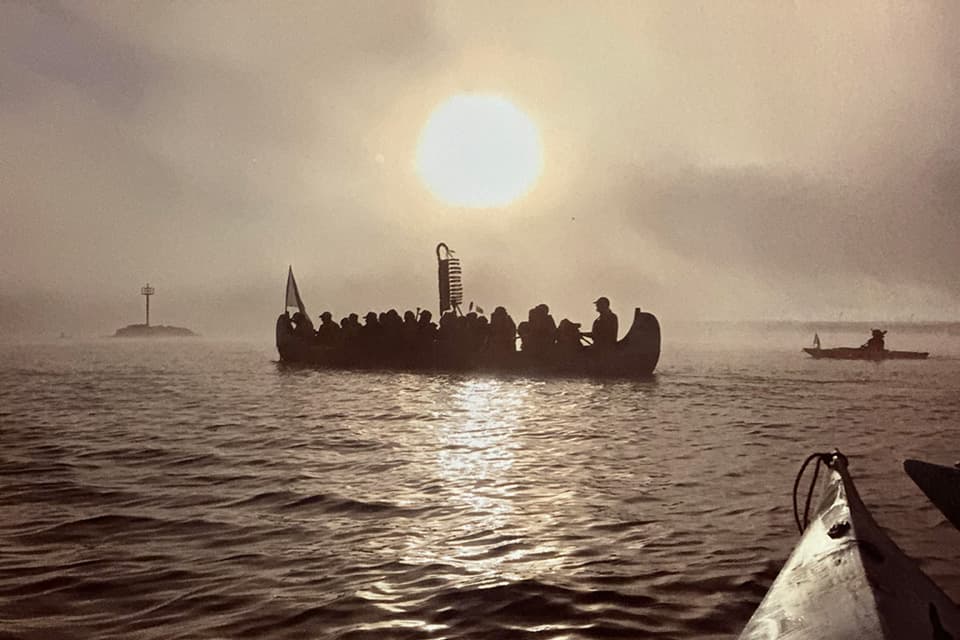

Thinking back to the teaching lodge, Recollet draws on another Anishinaabe analogy shared by Elders.

Our Ogimaak speak of our full canoe—full of our language, our laws, our ceremony, our resources. They say our canoes were so full that you could only see the top of the canoe.”

—Cheryl Recollet

Recollet will play a role in redefining this future for Anishinaabe people, and in supporting the resurgence of her community.

“Our canoes will be full again.”

UVic's PhD in Indigenous Governance is the only program of its kind in Canada. Visit the program page for details and application information.

Photos

In this story

Keywords: Indigenous, government

People: Cheryl Recollet