Whale bones tell visceral tale of orca history

- Stephanie Harrington

If a picture is worth a thousand words, how do you quantify the experience of holding a whale skull?

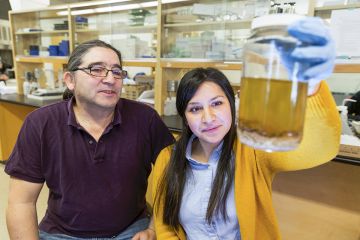

Students in Jason Colby’s class, “From oil to icons: the history of people and whales,” had some heft added to their learning recently at the Royal BC Museum (RBCM).

Museum curator Gavin Hanke treated undergraduate and graduate students in Colby’s course to an exclusive tour of the fourth floor, where some of the museum’s whale specimens are stored.

The RBCM houses 22 specimens of orcas, also known as killer whales—the largest collection on the Pacific coast—as well as porpoises, belugas and dolphins.

“This is a major stop for orca nerds,” Hanke said. “Scientists from all over the world come here for their research.”

Bones testament to fragile local orca population

Hanke, a vertebrate zoology expert, took students through the museum’s inventory of whale specimens, including baleen plates and skeletons that date back to the 1940s.

Recent specimens include Rhapsody, the pregnant orca found dead in 2014 near Comox. Her fetus, which was full-term, is also stored at the museum—the two whales testament to the increasing fragility of the endangered southern resident orca population.

Students had the opportunity to hold whale teeth and to examine the enormous vertebrae that form an orca’s spinal column. Graduate student Tim Cunningham lifted a juvenile orca’s skull in his arms.

“It’s not light,” he joked.

How to prepare a specimen

Hanke outlined the laborious process of preparing a specimen for storage. He told students that after a necropsy, scientists remove the carcass’s tongue, organs and flesh, which are sent to the hazardous waste section of the landfill.

“PCBs, metals and whatever’s accumulating in their food chain magnifies through them,” Hanke said.

The carcass is then buried in compost while Hanke says “nature does its bit.” Eventually, the specimen comes back clean and ready for storage. Contrary to orcas’ violent image, Hanke told students that killer whales are “very community-minded.”

“When one is crippled, they will feed it. They’re better people than people, that’s for sure,” he said.

Visceral—and eerie—history experience

Colby, an associate professor in the Department of History, whose book Orca: How We Came to Know and Love the Ocean’s Greatest Predator was published earlier this year, says he wants history to have a physical dimension for students.

“The work of history is often a disembodied process. You’re often dealing with documents,” he said. “It’s something visceral for them to come here and touch the bones.”

Graduate student Nate Ruston wasn’t bothered by the smell of the fourth floor—which Hanke described as “rancid fat”—or the look of the bones.

“It’s a little eerie, but it’s fascinating too,” he said.

The public will also have the chance to see Rhapsody’s re-assembled skeleton when the RBCM opens a major exhibit on orcas in 2020.

Photos

In this story

Keywords: whales, ocean, wildlife, teaching, history, student life

People: Jason Colby

Publication: The Ring