Research aims to improve concussion diagnosis, treatment

- Mitch Wright

It’s game night at the local rink and cheering parents pack the stands as young players churn up and down the ice. Every scoring chance is hailed with roars of support. The barn falls eerily silent though, as one young skater racing for a puck loses an edge and slides headlong into the boards.

He gets to his knees unsteadily, then stands wobbly-legged and obviously shaken, and is rushed off the ice by coaches as white-faced parents are sprinting to meet them in the dressing room. They’re already worrying about concussion, a scourge throughout sports, but getting particular attention in the hockey world.

But if this young skater has sustained a mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), as it’s also known in scientific circles, it’s already too late to start evaluating the injury. Without baseline data on basic cognitive function, doctors, parents and coaches face a difficult task determining how severe the injury is, or if and how well a patient is recovering.

University of Victoria researcher Dr. Brian Christie is investigating whether video game-style software might offer a solution.

Christie, a professor in the Division of Medical Sciences and director of UVic’s new Neuroscience Graduate Program, is part of a team of researchers across Canada recently awarded $1.4 million over five years by the Canada Institutes of Health Research to conduct just that type of research. The goal is to standardize the terms and tools used to describe concussion patients to facilitate data comparisons across sites, and enhance investigations into long-term effects.

“There is enormous interest in concussion, both from a research perspective and from the public, and we’ve seen our project garner huge community engagement just by word of mouth,” says Christie, who was invited to speak on the subject at last fall’s Wickfest, an annual women’s hockey festival hosted by three-time Olympic hockey gold medallist Hayley Wickenheiser.

Christie was already working on a similar study, which will now feed into the CIHR-funded project, looking to validate a testing protocol for gathering accurate baseline information on cognitive function in youth hockey players. That effort partnered with the Victoria Racquet Club minor hockey program to test approximately 200 youth players ages 6 to 17 over the past year, using the Neurotracker software donated by Quebec-based Cognisens Inc.

Major professional sports leagues—including the NHL and NFL—use the program to improve athletes’ performance, but its potential as a low-cost, accessible option to accurately assess concussion symptoms and severity in youth athletes has Christie interested.

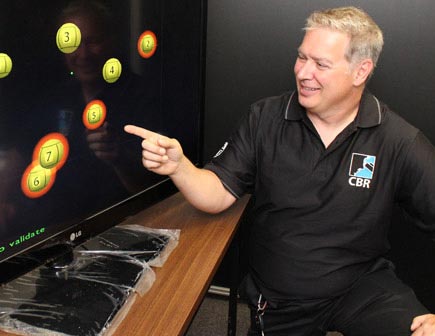

The game involves a screen with eight balls on it, with participants asked to track four as they move randomly about the screen. With each successful trial, the balls move faster and more difficult to follow. The recorded results could offer reliable baseline data on a number of different cognitive and perceptual abilities.

“Anytime they get a concussion, their ability to perform the game drops dramatically—almost in half—and as they return from a concussion we can see their speed in following the balls come back up,” says Christie.

Once reliable baseline data is established, it’s easier to determine if a player has sustained a concussion. Christie says it could also facilitate active recovery, through repeat testing to track cognitive improvements. Because the program involves testing a large group across a wide age range, it will result in year-by-year comparisons and longitudinal data, Christie says, adding that the UVic Vikes rugby team also began testing last year.

Standardized data will also help scientists better understand the symptoms that are the best prognostic indicators for poor recovery from concussion, Christie says. That knowledge will provide clinicians across Canada with more confidence in their diagnoses and empower doctors, parents, players and coaches to make better decisions about treatment, including when it is appropriate and safe for a patient to “return to play.”

“The majority of the traumatic brain injury research out there right now is based on adults, so we’re always speculating that maybe children have the same recovery times,” says Dr. Chand Taneja, a pediatric clinical neuropsychologist with the Queen Alexandra Centre for Children’s Health/Vancouver Island Health Authority. As the only practising board-certified neuropsychologist on Vancouver Island, Taneja sees most of the Island’s children referred due to neurological impairment. She is also involved in the CIHR-funded research project.

Christie, whose research also investigates how developmental disorders affect learning and memory processes, also believes there might be potential for the software to facilitate better perceptual awareness in developmental disorders like autism and fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, as well as having benefits for elderly drivers.

Christie spoke to parents, players and coaches about concussions during this week’s Ryan O’Byrne Charity Camp hosted at UVic’s Ian H. Stewart Complex, where the Toronto Maple Leafs defenceman also played minor hockey. The Neurotracker program was also be demonstrated during O’Byrne’s youth camp, with both guest coaches and camp participants given an opportunity to try it.

Photos

In this story

Keywords: concussion, athletics, sports, research, biomedical, health, brain

People: Brian Christie