Vanier Scholar advancing FASD diagnostics

- Angelica Pass

It certainly sounds novel: could a smelling test, easy enough to administer to young children, help diagnose Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD)?

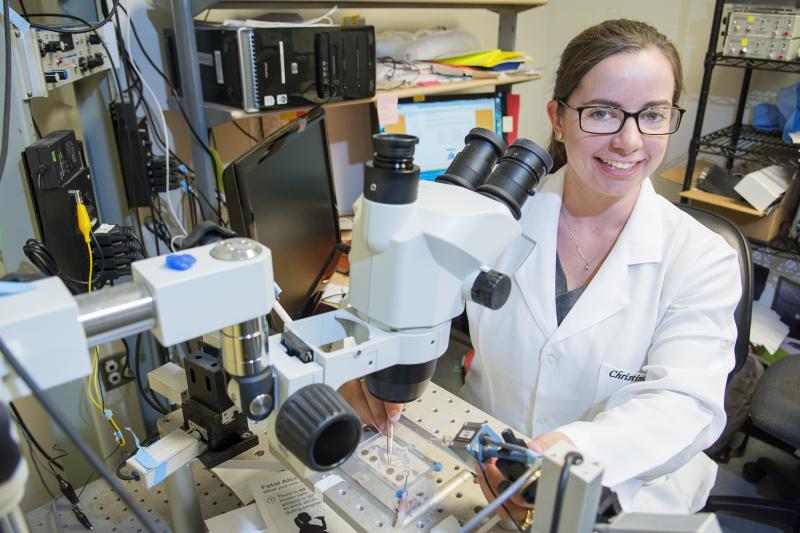

That possibility is taking shape, thanks to work done by UVic neuroscience PhD student Christine Fontaine.

Her research is so promising that Fontaine was selected as the university’s 2014 Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship recipient—a scholarship created to attract and retain world-class doctoral students, which awards $50,000 annually for up to three years.

“It feels amazing and surreal. I wasn’t expecting it at all,” says Fontaine, who notes that the scholarship also reflects the quality of research happening in the Neuroscience Program. “It’s a young program and there are now two Vanier scholars enrolled, Leigh Wicki-Stordeur and myself, which is really incredible.”

Fontaine works in Dr. Brian Christie’s lab, where significant research is being done into how FASD changes the way neurons grow and develop in childhood and into adulthood. The goal of this research is to better understand the disease in order to target therapeutic treatments. Early identification means early treatment, but as a spectrum disorder, the structural and functional impairments caused by FASD are not always easy to define.

A simple test for FASD in early childhood could ultimately make all the difference for diagnosis and treatment, and that’s where Fontaine’s research comes in. Fontaine studies how fetal alcohol exposure modifies levels of antioxidants in the brain and how this changes neural functions such as learning and memory. Working with rat models, Fontaine has noticed that the reduction in antioxidants from fetal ethanol exposure seems to cause an inability to form smell memories. “Rodents see the world through their sense of smell so it’s detrimental when anything interrupts this sense,” she says.

In terms of the applications for human children, studies have shown that children with FASD have difficulty distinguishing household smells. Therefore, identifying olfactory deficits in animal models opens the door to the potential for diagnosing FASD in human children through a simple smell test. “This would make a novel and easily accessible way to diagnose the disorder,” says Brian Christie, Fontaine’s advisor and chair of the neuroscience program.

Working with Christie, as well as her desire to stay near the ocean, were Fontaine’s primary reasons for coming to UVic. And the campus is lucky she did, explains Christie: “Christine’s research has been very well received in the scientific community. Already, one of the leading experts in FASD modeling and a leading olfactory expert have both expressed interest in being on her thesis committee. This is great exposure for UVic and the neuroscience program.”

Fontaine knew from a young age that she wanted to work in a research lab. The Women in Science and Engineering (WISE) chapter in Newfoundland and Labrador, where Fontaine grew up, sponsors a summer program that allows girls to work in research labs for eight weeks. While still in high school, Fontaine participated in this program and worked in a behavioural neuroscience lab, where she got her first taste of lab work. “I was hooked; they actually had to pry me away from the lab to go to social functions,” Fontaine laughs.

She is still a director for the WISE summer program and thinks it is important to give back to other young women who might not yet know their passion for science. “I honestly don’t know where I would have been without this program. My advice to young women is to pursue their passion for science, get involved in every opportunity and ask questions.”

Photos

In this story

Keywords: alcohol, graduate research, neuroscience, disease, Women in Science and Engineering

People: Christine Fontaine