Bearing witness and bringing awareness to migration through art and anthropology

- Anne MacLaurin

(This article contains descriptions and information that may be disturbing to some readers)

Physical exhaustion, heat exposure and dehydration are everyday experiences for migrants making their way across the Mexican-US borderlands. Many perish as they attempt to cross the deadly stretch of desert trying to reach asylum. UVic anthropologist Melissa Gauthier and her third-year undergraduate students took part in a participatory art project last term called Hostile Terrain-94 (“HT94”), created by US anthropologist Jason De León and the Undocumented Migration Project, as a way to learn about migration and the economic underworlds.

UVic takes part in global installation

Gauthier uses art to support her teaching about illegal economies and how people make a living in the devastating shadows cast by the globalization of human smuggling.

The HT94 installation is taking place collectively at a large number of institutions across North America and globally in 2021 and through 2022.

As a hosting partner, UVic’s Department of Anthropology brought the HT94 exhibit to our university in January 2022, following delays related to the global pandemic.

UVic hosted this installation, one of only two universities in Canada to do so.

—UVic anthropologist Melissa Gauthier

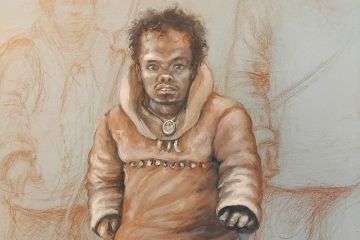

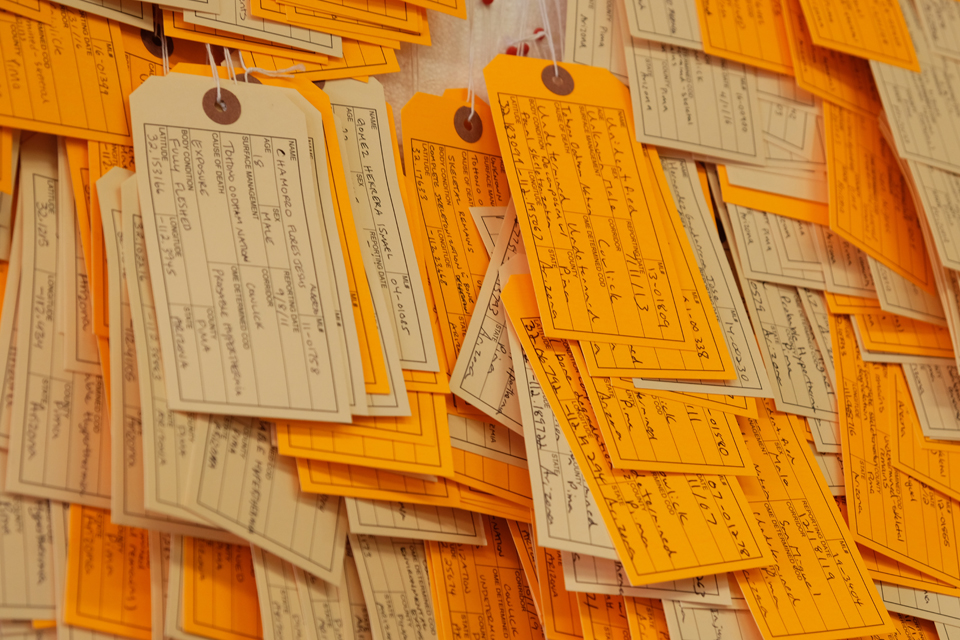

The HT94 participatory art project invites students to bear witness and remember the people who died trying to find a better life, as well as the families who still mourn their loss. Gauthier’s students spent weeks handwriting toe tags (including each person’s name, age, cause of death and location of recovery of the deceased’s body) for all 3,200 people who perished between the mid 1990s and 2019 in the harsh environment of the Sonoran Desert.

“I use the work of De León in my courses and UVic is invested in a variety of interdisciplinary approaches to learning,” Gauthier adds.

Students were also directly involved in the construction of the HT94 installation at UVic by carefully attaching each single toe tag to the 16-foot-long wall map. The tags are geolocated on this wall map of the desert, showing the exact locations where people’s remains were found.

Witnessing firsthand the effects of human smuggling

Fourth-year honours anthropology student Mariana Montes said the class made her think deeply about the circumstances and vulnerability of migrants who come from Latin America.

In the names that I wrote in each toe tag I saw my brother, my sister, my father, my cousins, my friends and people whom I have encountered throughout my life…I felt a deep empathy and grief for those who lost their lives and their family members.

—UVic undergrad student Mariana Montes

Throughout the semester, much of the physical and emotional labor involved in filling out the toe tags occurred both inside and outside of the classroom. Several students in the class reported filling out toe tags with their own friends and relatives – and having meaningful conversations with their loved ones about these deaths and the hundreds of still unidentified people whose remains have yet to be reunited with family members.

“In my course, I use a wide range of ethnographies on unauthorized border crossings to help students critically rethink simplistic narratives of clandestine migration,” says Gauthier.

“The Hostile Terrain 94 installation enabled students to witness firsthand what has been described as the murderous effects of border management regimes,” adds Gauthier.

“Participating in the Hostile Terrain exhibit felt like a good first step towards bringing awareness to the issue, and hopefully in the future, less and less people lose their lives trying to cross the US-Mexico border,” says Montes.

The installation will continue to be shown at 150 locations around the world through 2022.

Find out more

Photos

In this story

Keywords: international, art, migration, anthropology

People: Melissa Gauthier