Syrian men use photography to turn eye on mental health

- Stephanie Harrington

The men come from across Syria, from all walks of life. In their home country, they worked in dentistry, civil engineering, architecture, business and the arts. Some are fathers; some are sons; others wait for loved ones to join them.

They are united by their shared experience of forced migration and their hopes of building a new life in Canada. They fled one of the century’s most brutal wars, a conflict that has killed more than 600,000 Syrians and displaced millions more. From 2015 to 2018, 51,000 Syrian refugees were resettled in Canada through refugee or asylum immigration streams. About 4,400 Syrians settled across British Columbia in 65 communities.

University of Victoria President’s Chair Nancy Clark has been working with 11 Syrian men who have resettled in the lower mainland of Metro-Vancouver and Victoria on a two-year Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) study. Exploring Syrian Men’s Mental Health and Participation in Labour Employment: A Community Participatory Arts-Based Project uses photography to explore the social determinants of Syrian men’s mental health and highlights how the intersections of masculinity, forced migration and resettlement shape men’s experiences of economic integration.

“The Syrian refugee crisis is one of the largest humanitarian crises in history,” says Clark, who is director of UVic’s Social Justice Studies program and an associate professor in the School of Nursing.

Like other newcomers and people who experience forced migration as a result of war and conflict, and who arrive through Canada’s various immigration streams, Syrian groups continue to experience significant employment and income insecurity creating barriers to their health and wellbeing.”

—Nancy Clark

Barriers to integration

Despite being professionals in Syria, many of the men involved in the project now work in low-skilled jobs, often as delivery drivers or in manual labour, to survive.

Clark says a lack of recognition of the men’s credentials prior to coming to Canada, discrimination, and working in ‘survival jobs’ creates barriers to economic integration and their overall well-being. She says long hours, lack of mentorship and low-skill service industry work can impede the men’s ability to improve their English skills, which are needed to integrate into the Canadian job market.

To date, little research attention has focused on the mental health of refugee men and gendered effects of migration and resettlement. Most research adopting an intersectional analysis tends to focus on women and girls, neglecting the whole family system.”

—Nancy Clark

The study’s findings suggest that the mental health of Syrian men is shaped by structural conditions, as well as their lived experience of language barriers, time, isolation, belonging and gendered roles.

“For men, particularly men of Arabic descent, culturally it’s their responsibility to provide childcare and to provide to their family,” Clark says. “However, men’s gendered roles may be overshadowed by broader notions of masculinity and is often neglected by employers.”

Photography as research tool

A key part of this community-engaged participatory project is that the men actively collaborated in the research process rather than being studied as “subjects.” The study’s findings draw from the Syrian men’s recommendations for policy and practice change.

Three Syrian men participated as peer researchers alongside a community advisory team of employment specialists, mental health counsellors and programmers in settlement services agencies in BC, including Options Community Services.

To build trust and community engagement with the Syrian men, the team organized peer workshops where the men learned photography skills from peer researcher Meer Mahmoud. When asked to take photographs that captured their experiences of integration in Canada, the men focused on their employment and the factors that shaped their mental health.

Peer researcher Nedal Izdden, who came to Canada in 2019 from Homs, in central Syria, says the project helped him reconnect with the Syrian community and heal from the trauma he experienced from the war.

“It’s a taboo for some people, especially for men, to talk about your mental health. For me, it was treatment to be part of this project. I came to more understanding of myself.”

—Nedal Izdden

Izdden trained as a dentist in Syria and co-founded the White Helmets humanitarian group during the revolution, but when he came to Canada, he discovered his credentials weren’t recognized. He eventually found work as a rideshare driver. Izdden realized that he shared many of the same problems as the other men, particularly around language barriers and the shame and isolation they felt at not being able to communicate easily.

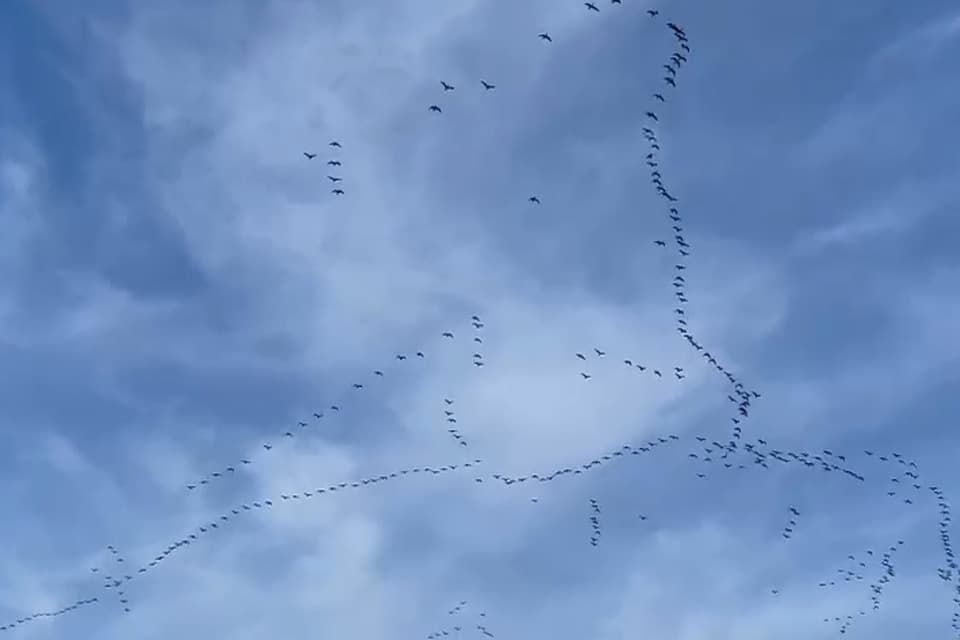

“The photos I took were very similar to other participants’ photos; it’s something like magic,” he says. “If you noticed the main elements, it was sunsets, it was time, it was empty streets, it was sitting alone on a beach or in a park.”

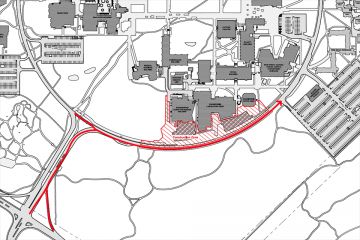

Clark says the men’s photographs represented intersecting dimensions that shaped their mental health. Photos of fences, for example, represented language barriers. Pictures of isolation represented a lack of support at work sites, family and friends left behind and discrimination. Photographs of belonging showed the men making time for picnics, enjoying sports or nature and being with friends and family.

Clark says that despite the diversity of men in the project, they shared common experiences.

Importantly, bringing men together also showed a gap in mental health supports for refugee men. An unexpected finding is that the research process contributed to increased support for men.”

—Nancy Clark

Calls to action

The book includes five calls to action based on study findings and promising new policies, such as the BC Government’s newly introduced fair credential recognition legislation that aims to reduce barriers for internationally trained professionals seeking jobs in the province.

Some of the men have overcome these barriers, including Kefah Georges, who worked as a civil engineer in Homs, Syria, before resettling on the lower mainland in 2018 with his wife and two children. Georges says he felt the best way to support his family was retraining as an engineer.

He enrolled in English classes and then went to the British Columbia Institute of Technology (BCIT) to take prerequisite courses, working 14 hours a day for seven months, so that he could apply for a bachelor’s degree. Five years later, Georges is now an engineer in training, working with a company as a land surveyor.

“Everything became easier for me after that qualification, after that companies accepted my previous experience,” he says. “I’m happy with what I’m working on here now.”

Clark says more research is needed for men who experience forced migration, and the factors that support mental health, such as belonging, recognition and respect, inclusion and social support. She calls for a whole-system approach. She says that means adopting community-based methods that integrate mental health with other social systems beyond the health sector and including the voices of people historically marginalized in mental health research.

Read more about this project on Futurum Careers.

Meet three of the participants

Nedal Izdden’s story

Nedal Izdden has lived three lives: One, as a dentist in Homs, Syria; A second life as co-founder of the White Helmets during Syria’s revolution; And a third life in Canada, where he came as a refugee in 2019.

Each of these transitions has brought a level of hardship to Izdden’s life unimaginable to many people in his adopted country.

“I didn’t just lose a home—I lost everything. It was very hard,” Izdden says.

His life changed in 2011 when Syrian President Bashar al-Assad started a brutal crackdown on civilians protesting his dictatorship. When the violence escalated, Izdden left his job as a dentist. He helped found the White Helmets (officially called the Syrian Civil Defense Force), a nonpartisan volunteer search-and-rescue force known internationally for their heroic work.

After visiting Canada in the spring of 2018 to meet government officials in Ottawa as part of his role with the White Helmets, Izdden found he could not return to his home in central Syria. He travelled to Turkey. His wife joined him later and they decided to apply to the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) as refugees. Izdden arrived in Canada in November 2019, just before the COVID-19 pandemic—alone, without a support network and needing work.

I struggled just to find myself again. It’s a totally new life, new language, new culture, new atmosphere, new weather, new traditions. Everything is new.”

—Nedal Izdden

Izdden eventually saved for a car and found work as a rideshare driver. But he struggled to deal with trauma from the war and his humanitarian work. He had debilitating panic attacks. He tried to isolate himself from the Syrian community in the lower mainland. When he was offered a peer researcher position with the UVic project, Izdden took the opportunity. He said the role helped him understand his life and to begin a new journey.

“I needed to say, okay, I had two lives, one life before the revolution, one life during the revolution, now I’m starting the third one. What do I need to do? Who am I?” he says. “I started to find myself again.”

Izdden’s wife has since joined him, and now he has a clear goal to retrain in Canada as a dental hygienist. He also wants to advocate for change to Canadian laws so that the credentials of foreign-trained refugees and immigrants are recognized here. In June of last year, Clark nominated Izdden for a prestigious Human Rights Award at the 2023 MOSAIC Awards, which he won.

At one time, Izdden would have described himself as sugar cane: Put him in the ground and he could grow anywhere.

After I came to Canada, I discovered I’m not a sugar cane, I’m an olive tree. I have very deep roots to my land.”

—Nedal Izdden

Diaa’s Kibabi story

Diaa Kibabi was 16 years old and living in Damascus when the war came to his neighbourhood. One day in 2012, he opened the door of their home and saw, 50 metres away, men dressed in military uniform, holding machine guns.

An hour earlier, Kibabi had been playing on his computer in his bedroom. He had spent almost two years away from school; it was too dangerous to leave their neighbourhood. His parents and four siblings got into their car and fled to their uncle’s. He left without his wallet, without ID. They never returned.

“We left in rush because we knew that a fight and bombing was about to start in the area,” he says.

After travelling to Lebanon and onto Cairo, Egypt, they applied to UNHRC for refugee status. Nine years later, his family was offered a chance to resettle in Canada. They had a family friend in Surrey. Kibabi was 25 when he arrived in 2022, full of hope and expectation. He appreciated Canada’s commitment to equal rights and equal opportunity. He appreciated the safety and peace of mind Canada offered him.

“I have solid roots. I like how secure and equal it is for everyone,” he says.

But once he started to look for work, he became frustrated. Despite speaking English fluently and having extensive work experience in sales, customer service and management from working in Egypt, Kibabi could not find work of any kind.

It’s very difficult to find a job. I have the skills. I have tonnes of experience and it means nothing here. It felt like they are saying to me, ‘We don’t want you. You’re not welcome here.’”

—Diaa Kibabi

His family friend told him about the Syrian men’s mental health study, and he signed up. He felt comforted that other men had similar difficulties finding work.

“It felt like you’re not alone suffering this problem. When they were speaking, they were expressing my feelings,” he says.

Through photography, Kibabi was able to express his loneliness. He left many friends and family back in Cairo. For one of his photos, Kibabi had his brother sit alone on some stairs, where people usually chat and have coffee. His brother’s sense of isolation is palpable in the photo.

Inspired by the other men in the group, Kibabi feels hopeful again. He has started to study business administration and eventually found work through a friend at a bakery, doing physical labour for minimum wage. He hopes to bring his fiancé to Canada from Syria in the near future.

“Participating in this project taught me to be more resilient and to be more patient,” Kibabi says. “Whenever I feel low or depressed or discouraged, I remember that they were able to surpass and persevere.”

Kefah Georges’s story

When Kefah Georges came to Canada, he felt he had no choice but to retrain as an engineer.

In Syria, he had his own office as a civil engineer in Homs and a home for his two children and wife. He lost it all during the revolution and was imprisoned by the Assad regime. He was released for health reasons three months later, after suffering terrible beatings that resulted in the loss of his kidneys. His sister donated a kidney to him. Georges’s family decided to leave Syria.

After being sponsored by a church, they arrived in BC in 2018. Georges was in his 50s, and he decided the best option was to return to school and get his credentials in Canada to work as an engineer again.

Despite having a master’s degree in civil engineering in Syria, his credentials weren’t recognized. Georges started studying English and went to BCIT to take courses to qualify for a bachelor’s degree.

“I needed that work to support my family here and the rest of my family in Syria,” Georges says. “When you tell me I can’t work [as an engineer] … that’s stressful for me.”

Five years later, he has completed his bachelor’s degree in civil engineering and is employed as an engineer in training with a company working as a land surveyor. His daughter is in university, his son is in Grade 12. Despite the hardships, Georges is grateful for the safety Canada has offered him.

“We’re alive. In our neighbourhood, we lived with death, bombs, explosions,” he says. “For me, now I feel comfortable because my kids have a future.”

The Syrian men’s mental health project helped him connect with other Syrian men and gave him a safe space to share his experiences.

In our country, no one can express himself. Now we are fearless to say everything we feel, no one will judge us. Other research has focused on women. They gave us space. And people who care about what we do and feel.”

—Kefah Georges

He hopes the project’s findings will create change and help other newcomers adjust to Canada and find meaningful work. Georges also hopes one day to sponsor his family remaining in Syria to come live in Canada.

Photos

In this story

Keywords: community, research, gender, health, human rights, international, mental health, racism, immigration

People: Nancy Clark