Whale shark tourism and the challenges of international research

Social Sciences, Graduate Studies

- Anne MacLaurin

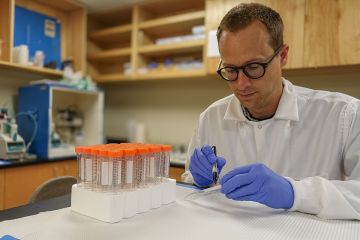

Every year, many UVic graduate students set off to do research in countries around the world. On occasion, they can face some common obstacles, such as achieving legitimacy with local communities and finding reliable translators. For UVic geography PhD candidate Jackie Ziegler, the big difference between her two experiences—in Mexico and the Philippines—was working with a local partner.

Ziegler studies the intersection between tourism and biodiversity conservation, with a focus on the marine environment. She investigated whale shark tourism first in Mexico for her master’s degree and then in the Philippines for her PhD.

Eight months in Mexico

“I taught myself how to read and speak Spanish before arriving at the site so I could communicate with people once there,” says Ziegler. “At the time, there wasn't a lot published and most of it was in Spanish.”

“I had to create relationships with local people and companies so I could get access to the tourists for survey collection,” she adds.

Six months in the Philippines

For both her master’s and PhD research, Ziegler studied the sustainability of whale shark tourism. And Oslob offered the perfect opportunity to study the impact of tourism on the docile whale shark, building on her master’s degree research in Isla Holbox, Mexico.

“During my PhD research in the Philippines, I worked with the Large Marine Vertebrates Research Institute Philippines (LAMAVE), a small independent NGO dedicated to the conservation of marine animals and their habitats in the Philippines,” says Ziegler.

“My research would have been impossible without the support of my excellent translators, the people in the local fishing villages where I stayed, and my research partner in the field, LAMAVE.”

LAMAVE found Ziegler a place to stay and provided excellent translators for her field work. This also meant she could learn more about local customs in the fishing villages where she stayed, whereas in Mexico, she did not have a local contact and therefore no advance preparation at the research site.

Whale sharks are an endangered species. We know very little about their life histories. We don’t even know where they breed. It is therefore important to understand both the benefits and costs of this type of tourism to ensure it is sustainable.

—UVic geography PhD candidate Jackie Ziegler

Oslob represents a unique research site where whale shark tour operators use krill as bait to ensure the sharks are in close proximity to tourists. This practice has sparked controversy.

“It is a $5M dollar industry attracting over 200,000 people each year,” says Ziegler, “and tourists are guaranteed a whale shark encounter in Oslob.

“And the Philippine government has still not decided whether it’s legal or illegal to feed them.”

Partnering with a non-profit NGO

During Ziegler’s fieldwork, LAMAVE provided legitimacy to local communities, as well as access to previous research and data. They also set up meetings with key people at the sites (e.g., mayors, leaders of the local organizations), provided local translators and helped get her research approved if needed.

“I am so grateful that LAMAVE provided volunteers to help collect my tourist survey data—over 1,200 surveys collected at two sites in a period of two months,” says Ziegler. “I didn’t have this support for my master’s research and therefore was unable to complete a planned comparative analysis of two whale shark sites in Mexico because the whale shark season was over by the time I had collected a sufficient number of surveys from the first site.”

Ziegler hopes her research will inform government policy makers, local villages and visitors about the ethics of feeding sharks for tourism purposes. She says more research is needed in this area since the long-term impacts of feeding marine wildlife remains unclear.

“I hope more graduate students will take on the challenge of international research in marine conservation,” says Ziegler.

“And if they do, I strongly suggest they work closely with local agencies right from the beginning,” she adds.

Photos

In this story

Keywords: international, wildlife, graduate research, research, biodiversity, sharks, geography

People: Jackie Ziegler