Communities rise to the challenge of citizen science

- Jody Paterson

On the rural properties of 19 citizen scientists in Metchosin, the work of verifying whether flying insect biomass is declining will soon be underway for another season.

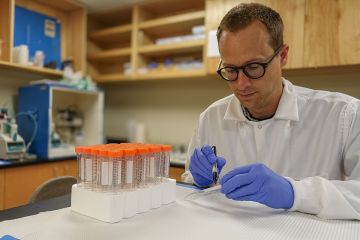

The Metchosin homeowners involved in University of Victoria entomologist Neville Winchester’s research were first recruited as citizen scientists in 2018. In the years since, they’ve trapped roughly half a million flying insects each season from May to October, helping Winchester in his efforts to establish a baseline and begin to identify insect biomass trends.

“We only have three years of data at this point, and we’ll need at least 10 before we can start making sense of any trends,” says Winchester, an adjunct professor and senior lab instructor in UVic’s Department of Biology. “But we know that many studies in Europe have found that the insect biomass is declining. Are the same trends occurring here? This has major implications on many biodiversity fronts, including pollination and decomposition.”

A recent study of 63 protected areas in Germany found a 75 per cent decline in the volume of insects over a period of 27 years. A 2019 global review of comparable research identified a rate of extinction for insects eight times greater than that of mammals, birds and reptiles, with disturbing implications for the food web and vital ecosystem processes.

Using the same kinds of traps as the German study, participants in the Metchosin project empty the Malaise “passive flight interception” traps on their property weekly, and twice a month bring their catches to Winchester, who weighs and sorts them into six categories comprised of hundreds of species.

Collaborating with citizen scientists increases science literacy and provides researchers with much larger data sets. In 2017, Ocean Networks Canada at UVic enlisted more than 500 citizen scientists to monitor real-time video from underwater cameras off the coast of Tofino and count the deep-water sablefish they spotted in that time.

Winchester says his work strives to develop “a community-driven environmental project model” that engages and trains citizen scientists in rural communities to be part of monitoring and supporting biodiversity and conservation.

UVic biology student Nathan Heuver is working with Winchester on the Metchosin project to do a “deep dive” on one particular species, the stilt-legged fly, while Winchester’s broader data collection seeks to establish whether Europe’s sharp decline in insect volumes is also happening here.

“Why are they declining? Habitat loss, insecticides, changes in weather, climate change – there are several reasons for the decline,” says Winchester. “A lot of biomass impacts tend to relate to habitat use. That’s why we chose Metchosin for this work. It’s a green community, and people have been really enthusiastic and want to see how the insect fauna is reacting to habitat use in the district.”

Climate change obviously has an impact on ecosystems, says Winchester. But the European research confirms that widespread use of industrial pesticides is even more of a factor in decline, he notes, along with habitat alteration due to development, industrial agriculture and logging.

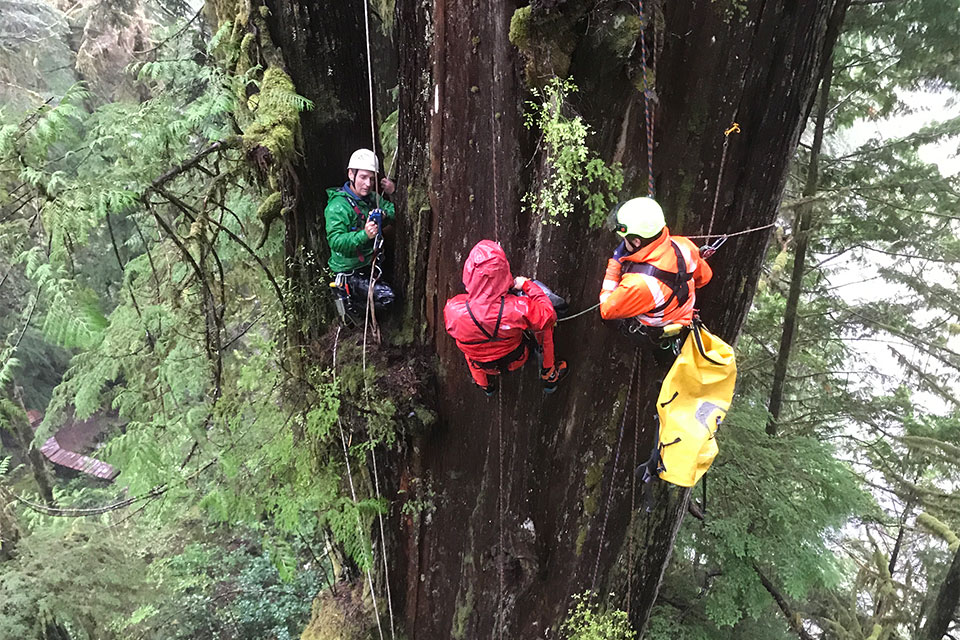

Winchester spent years researching insect populations in forest canopies around the world for his own PhD - work that was recently featured in The Nature of Things’ “Wild Canadian Weather” series. “We climbed over 6,000 trees in 12 countries,” he says. “A lot of what we learned through the canopy work is applicable to the Metchosin Flying Insect Biomass Project.”

There are no tree tops in this latest work, however. Traps are on the ground.

Heuver chose to study the stilt-legged fly because so little study has been done on it. “It’s a chance to learn more, and put a magnifying glass on a single species,” says the fourth year Bachelor of Science student, who is doing his honours thesis on the fly.

He “jumped on the opportunity immediately” to be part of the Metchosin research after learning about it in his entomology class with Winchester last year. Heuver has found 300 stilt-legged flies among almost a million insects gathered in 2018 and 2020, the years he’s studying.

Winchester hopes for a day when similar data collection is going on in people’s back yards right across the region, province and country.

But with traps costing $300 each and only the Metchosin Foundation helping out with funding for Winchester’s work to date, efforts are confined to Metchosin for now. Winchester aims to collect data until at least 2060, and is counting on his team of citizen scientists to recruit future generations into the work to keep building the data set.

Photos

In this story

Keywords: research, biology, climate, community, environment, sustainability, administrative, student life

People: Neville Winchester, Nathan Heuver

Publication: The Ring