Brain burnout

- Suzanne Ahearne

Cheap, portable technology measures cognitive fatigue

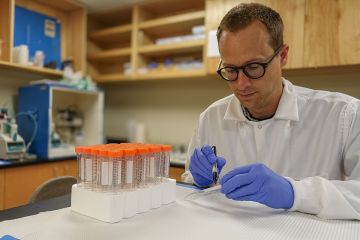

What if you could peer inside people’s brains to see what’s going on? This may sound like a sci-fi pipe-dream, but to University of Victoria neuroscientist Olav Krigolson, the brain is his “final frontier” containing the last great mysteries of the human body.

From his Theoretical and Applied Neuroscience Lab at UVic, Krigolson is boldly going where only multi-million-dollar technology has gone before. Krigolson has developed a unique mobile electroencephalography (EEG) system to investigate what’s happening in our brains when we’re tired, stressed, oxygen-deprived, struggling with dementia, concussed—or on Mars.

His research is making it possible to easily and cheaply identify when we are in our best brain states for learning and processing difficult information, when we are at the greatest risk of making mistakes, and when our cognitive abilities are declining.

In one of his first studies, Krigolson measured the effects of fatigue on medical residents doing acute care in the emergency room at Victoria’s Royal Jubilee Hospital.

When doctors and nurses put in long, gruelling shifts in the ER, they make mistakes. And when they make mistakes, people die. It's really that simple and harsh. We already know this is happening. Many studies have shown this. The problem is, how do you detect it?

— UVic neuroscientist Olav Krigolson

Krigolson explains that the pattern of EEG data in each brain state—be it depression, fatigue or dementia—is distinctive. The system his team developed can identify each of these states by reading the brain waves.

What surprised the research team was that of the more than 2,500 people they’ve monitored so far across multiple occupations, few were able to accurately assess their own fatigue levels—many of whom exhibited brain states equivalent to being legally impaired. The current gold standard is to literally ask, “Are you too tired to work?” Clearly, that’s inadequate, he says. “Providing an objective way to measure that is going to save lives.”

“And in terms of having maximum impact across multiple types or workplaces, the technology has to be accessible, low cost and easy to use,” Krigolson points out.

To do this, he co-founded Suva Technologies.

In 2017, the UVic spin-off company launched PEER, the world’s first iOS application designed to collect research-grade EEG data using an adapted version of a commercially available wearable device that measures brain waves.

Funded by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada grants, Krigolson's team has used this adaptable system to explore a growing number of human performance and health applications.

Two of the most promising applications are in concussion research and in monitoring mild cognitive impairment (MCI)—a precursor to dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Currently, Krigolson is part of a yearlong pilot project with Island Health and University of British Columbia neurologist Alex Henri-Bhargava to demonstrate if mobile EEG could be used to reliably assess and monitor MCI. If it can, it would mean improved outcomes for more people dealing with memory loss.

The long-term goal: “To have a device that anyone can use, like a blood pressure monitor or a Fitbit, to track your brain health,” says Krigolson. This sci-fi scenario may not be too far off.

EdgeWise

There are many possible uses for this technology that could have broad impacts for people who face long work hours and require critical decision- making skills in occupations such as emergency room physicians, pilots or heavy equipment operators.

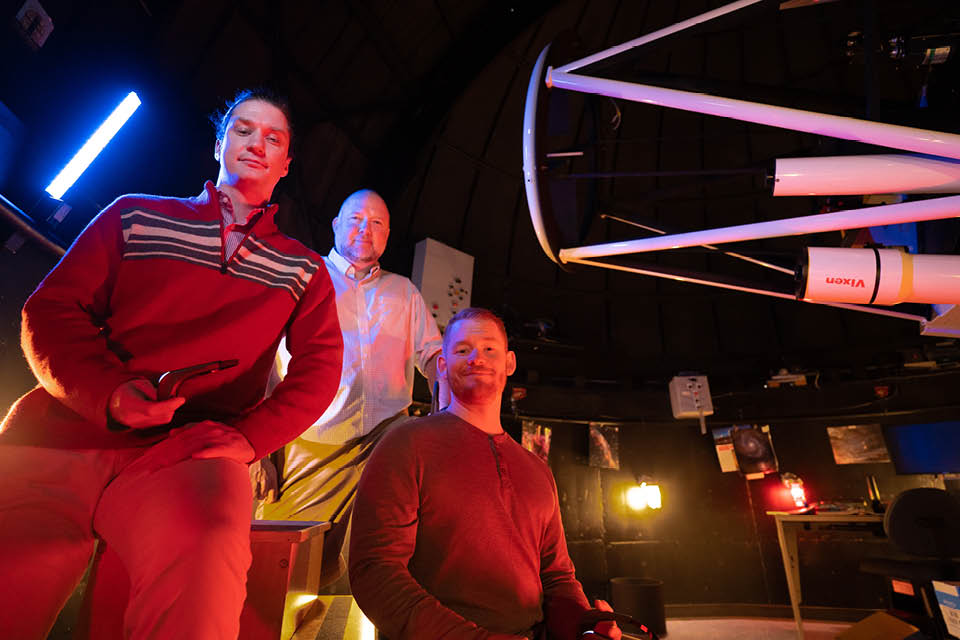

Last year, an all-Canadian, multi- university research team took the technology to a simulated Mars environment to test whether the system could be a reliable way to monitor astronauts’ brain function during missions in outer space—something NASA currently doesn’t have an objective way to determine.

During the weeklong NSERC-funded simulation at the Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation (HI-SEAS) habitat, six scientists wore the EEG devices and tracked changes in their memory, decision-making, learning and attention.

Krigolson co-led the team with two UVic PhD students Tom Ferguson and Chad Williams (pictured), and scientists from UBC Okanagan, University of Calgary, University of Hawaii and International MoonBase Alliance.

“Our analysis will literally tell NASA: astronaut X should not do this today; astronaut Y is in better shape to do that. The system can tell them if they are depressed and need help, or if their stress is reducing their function,” he explains.

Krigolson is hoping to test the technology in a longer simulation of up to a year.

“And if that works,” he says, “hopefully it’ll go into space, either as part of the Mars mission or at the International Space Station.”

Photos

Videos

In this story

Keywords: research, brain, health, mental health, technology

People: Olav Krigolson

Publication: knowlEDGE