Hanging out in Shakespeare’s ‘hood

- Patty Pitts

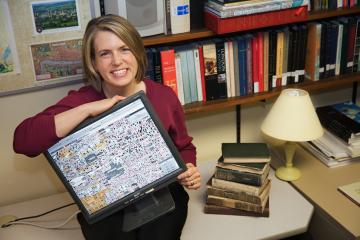

Frequent in the plays of William Shakespeare and his contempories are references to the playwright’s “neighbourhood,” the teeming 16th-century streets of London. For years UVic English professor Janelle Jenstad struggled with how to make these references more relevant to her undergraduate students. Then she discovered the solution in a 450-year-old woodcut map in London’s Guildhall.

Since getting permission to photograph the highly detailed Agas map in sections in 1997, Jenstad has completely digitized it and the resulting, and constantly evolving, website “The Map of Early Modern London” recently won rave reviews in London’s Evening Standard newspaper.

“I’m not a computer person, but I was so committed to this project that I taught myself to be a computer person,” says Jenstad, who admits she nearly abandoned the map project at one point when technological change required her to overhaul her entire content. “There’s so much interest in it. It has obvious value beyond its function as a teaching tool.”

In the same way that maps were used in Shakespeare’s time to build a community identity among newcomers flocking to London from the country, Jenstad’s digital map is attracting a widening circle of online devotees.

“Complete strangers email me all the time. Some have even used this site to navigate modern London. And there are many amateur historians out there with interesting information culled from archives and parish records,” says Jenstad, who currently only includes historical and literary data that can be verified. She’s in the process of creating an editorial board to referee unsolicited, but appropriate, additions.

Jenstad and her student assistants have created multiple layers and limitless potential for the website by tapping into technological advances that allow for more editing flexibility and efficiency. They also drew on the helpful expertise at UVic’s “wonderful” Humanities Computing and Media Centre.

“At the moment, the site is like an encyclopedia with blank pages waiting to be filled in,” she says. “Each page is linked to the map, which I could never have done in a print medium.”

Starting with the original woodcut drawings that depict a bird’s-eye view of individual houses, rowing boats on the Thames and citizens going about their daily chores, Jenstad has built links to historical facts about individual buildings, the histories of the streets and literary and historical references about famous, and not-so-famous, people who made appearances in the area.

“The Triumphs of Truth,” an addition by one of Jenstad’s students, uses the map to trace the elaborate procession of London’s Lord Mayor, for whom allegorical pageants were staged at various sites. Instead of just reading about the daylong event, visitors to the website can view the neighbourhoods the procession visited and click on links to learn more about the various stops.

Jenstad has a formal partnership with the Guildhall Library, which has since provided her with better scans of the Agas map, and includes a link to its online digital database on her website. No stranger to London, Jenstad estimates she’s visited it eight times, but she relies on a more up-to-date map on her trips.

“When the libraries close, I walk and walk and walk,” she says, “with my London A to Z in hand.”

Visit “The Map of Early Modern London” at mapoflondon.uvic.ca.