Artistic space

- Kate Hildebrandt

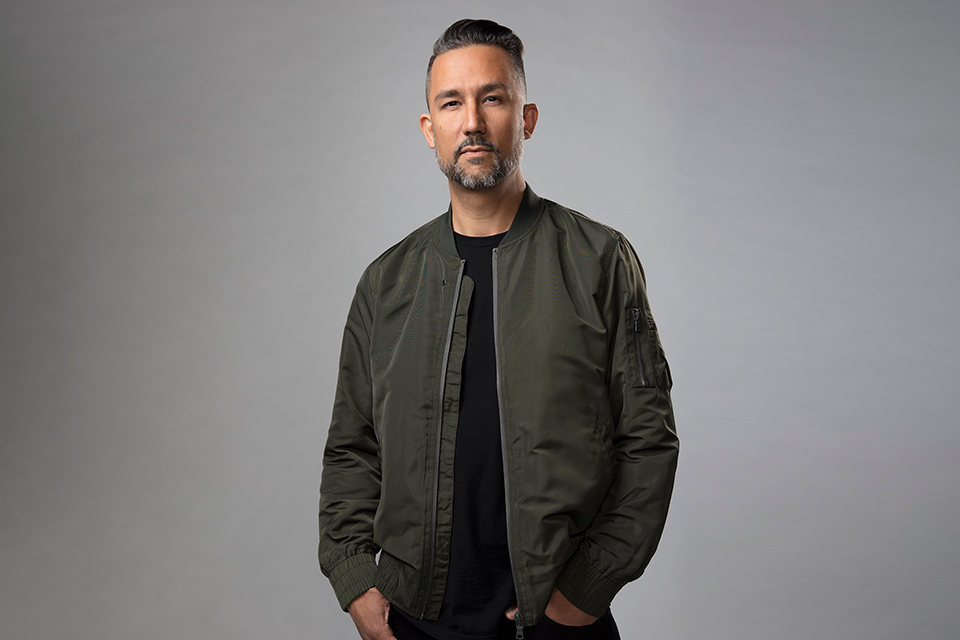

Media maker, storyteller and scholar Jarrett Martineau puts Indigenous creative arts in the spotlight—and the world is watching.

Jarrett Martineau is a leading influencer within the Canadian media scene, having produced several high-profile projects in the last 15 years. His is a story of remarkable success for someone who has barely brushed his forties. Even so, this music producer confides his most favourite place to be right now is not in the spotlight, but hidden from view in a spot off stage, watching the shows he represents.

“There’s this magical 45-degree angle where you can see an artist in their element, you can see the audience reacting, and you can feel the effect the audience has on the artist. I love being witness to that magic. It’s powerful.”

The Indigenous Governance graduate (MA ‘11, PhD ’15) is nêhiyaw (Plains Cree) and Dene Suline. He is the son of a white mother and a Cree/Dene father, and while he leads a busy life in Toronto, he returns home regularly to Frog Lake First Nation, Alberta, to visit family and reconnect with his community and traditions. Even his decisions about moving to Toronto and going back to university were matters first discussed with Elders and put into prayers. “I need to come home regularly,” he said.

Martineau hosts Reclaimed, a CBC radio show devoted to Indigenous music, runs his own record label, Revolutions Per Minute (RPM), and his own web-based multimedia channel. He has hosted TV shows, documentaries, and writes scholarly papers. He is a popular guest speaker at universities. He is also a key figure fanning the flames of resurgence through new and emerging Indigenous music.

Case in point: Jeremy Dutcher, 27, Canada’s latest recipient of the Polaris Prize, is a stellar example of such talent who recorded his first single under Martineau’s RPM label. Dutcher also lives in Toronto and has been interviewed by Martineau on CBC.

Dutcher is a classically-trained tenor from the Tobique First Nation in northwest New Brunswick. An elder told him he could hear original songs sung by his ancestors at the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Quebec. There, Dutcher found a collection of 100-year-old wax cylinder recordings of traditional Wolastoqiyik songs. For the next five years, Dutcher re-recorded these songs, music he had never heard before in a language he did not know.

“I can’t help but notice how, within 30 seconds of hearing Dutcher’s music, it makes people cry,” says Martineau. “There’s something about what he’s doing that connects deeply with many different audiences.” Martineau says his other favourite place to be is in that moment when an artist he knows and admires, like Dutcher, seeks him out.

From the classics to hip-hop, folk, rock, pop and rap, Martineau views the entire North American Indigenous music scene as a collective voice for unravelling the old constraints of western colonialism. This vision is reflected in his early work when, in 2000, he co-founded Vancouver’s New Forms Festival, an annual modern art and music festival. Martineau went on to host and produce segments of Brave New Waves, an acclaimed CBC music series about Canada’s underground arts and music world. He also hosted CBC’s multimedia lifestyle series called Zed Real, and was nominated for a Leo award by BC’s Film and TV Association.

Yet, he decided to put his burgeoning career on pause to study Indigenous Governance at UVic. This was when then Prime Minister, Stephen Harper, issued an apology to Indigenous people for Canada’s role in creating the residential school system. Martineau felt inspired to learn more about self-governance. He felt, too, that people weren’t ready to hear this new Indigenous sound, nor were Indigenous communities ready to share it.

“It’s interesting to see how things have played out, especially after I completed my PhD. My career soared and our record label just took off.” In 2010, he co-founded his contemporary Indigenous label, RPM, which is also a web-based, global new music and artist collective. “No one was doing this,” he says, still astonished. “There was nowhere you could go to find new Indigenous artists.” But all that has changed, thanks, in part, to his determination. “It’s all happening right now just as I had hoped. The advocacy and the supports are there within the community.”

“And it’s not just my work that’s evolving,” he says. “These kinds of projects, these cycles of continuation, this new thinking is happening throughout the Indigenous community.”

Martineau helped influence that thinking with first-person reporting using new media. Premiering on VICE in 2017, his documentary series Rise brought viewers into Indigenous communities to meet people and hear their testimonials on what it takes to protect their homelands and resist colonization. He plans to continue hosting Reclaimed for CBC Radio and aims to build an even larger audience. RPM is also poised for new ventures in live music festivals and he is looking for partners here and overseas. Plus, there are a number of new RPM releases coming out as the work of Indigenous artists gains wider exposure. Eyeing new business opportunities on the horizon, Martineau sees a need for Indigenous artist management services and festival programmers, opportunities he’s not likely to pursue.

“There is a belief in business that you must always expand or you’ll be forgotten. Our approach at RPM is different. We want to take on fewer artists, as that affords us a slower, deeper way of working,” says Martineau. “This is part of the reason why we do our ceremonies. It brings us back to our core teachings.” Martineau notices how his own pace slows when at home in Frog Lake. “I am reminded that the big city does not have to be about doing all things for all people. I can do things at my pace and still succeed.”

“Jarrett wants to do things right,” says professor Jeff Corntassel, previous director of UVic’s Indigenous Governance program and now with the Indigenous Studies department, who worked closely with Martineau during his four years of study.

Corntassel describes Martineau as an Indigenous “cipher,” one who finds ways to share teachings and inspire others to learn the symbols and icons of Indigenous art. Corntassel notes how a wider audience has come to appreciate Martineau’s deep understanding of the ancient music-dance story, wherein the battle cry for change is woven as a melodious song.

I believe I have a responsibility to connect with Indigenous communities by reaching out to as wide a geography as possible, tapping into vast genres and playing those artists who have not been played, hearing that language that has not been heard.

—Jarrett Martineau, UVic alumnus

Martineau is a Fulbright Visiting Scholar at Columbia University and was a recent guest lecturer at City University of New York’s Indigenous New Media Symposium, yet he chose not to go the typical academic route. “Instead,” says Corntassel, “he found a way to apply his learning toward something that wasn’t confined by institutional boundaries.”

“He’s a natural leader,” says Corntassel, “and he wants to articulate the struggle Indigenous people face in this colonial world in a way that is powerful and unique.”

Martineau’s widely read dissertation examines the role of art-making and creativity in Indigenous struggles for decolonization. Martineau says he continues to live out his UVic dissertation every day.

“It’s a continuous state of work and study, asking questions and finding answers in profiling an amazing range of talent across the Indigenous music sector.”