Our freedom to read—Pass it on

- John Barton

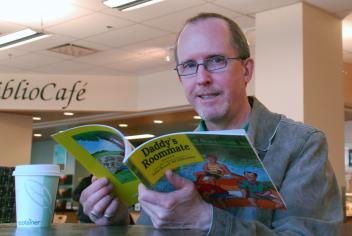

In the last week of February, I “released” Michael Willhoite’s pioneering children’s book, Daddy’s Roommate, somewhere in Victoria.

A vividly illustrated picture book aimed at 2- to 8-year-olds, it recounts the story of a kindergarten-aged child who, after his parents’ divorce, begins to spend his weekends with Daddy and Daddy’s new “roommate.” The boy observes that they work, eat, sleep and shave together; they even share looking after him too. Frank, the new man in his and Daddy’s life, is as adept as Daddy at making peanut-and-jelly sandwiches and reading stories. Crucially, in a gesture proving that neither tolerance nor maternal love is skin-deep, it is his mother who explains to him what being gay means and that it is “just one more kind of love.” The boy decides if Daddy and Frank are happy, then so is he.

Published 20 years ago by Alyson, Boston’s world-renowned queer press, Daddy’s Roommate was one of the first children’s books to “illustrate” gay and lesbian parenting in a positive light. It also holds the distinction of being number two, ahead of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Of Mice and Men, in the American Library Association’s list of the 100 Most Frequently Challenged Books of the 1990s. Though now in its umpteenth printing, it is a postmodern-day classic whose easy availability we must still guarantee.

I was one of 26 staff and students from the University of Victoria who released similarly controversial books during the 26th annual edition of Freedom to Read Week (Feb. 21–27), the Book and Periodical Council’s (BPC) long-celebrated, nationwide initiative that aims to raise awareness of, and foster commitment to, the right to read and intellectual freedom.

These releases involved leaving our books in coffee shops, laundromats or bus shelters anywhere in the city or in the world. Through BookCrossing, a book-sharing website the BPC partnered with this year, anyone who finds one of them can discover how far or near it may have already travelled by logging in with the identification number on the bookplate on the back cover (my release’s ID is 679-7786341).

BookCrossing encourages all “finders” not to be “keepers,” but to abandon their books somewhere—after reading and recording their impressions of them on its website—so that over time they will have stories to tell independent of the ones printed on their dog-eared, coffee- or tear-stained pages. Presumably, the 26 UVic “releases,” like fingerlings from a hatchery, shall have the opportunity to voyage far.

Not only as a writer and editor, but as a gay man (albeit not one who’s a father), I feel it is essential to lend my support to a child’s or adult’s right to read Daddy’s Roommate, a book I would gladly see in any personal, public or school library alongside the open-ended largesse of Dr. Seuss. After all, at least 10 per cent of the Whos in Whoville must be lesbian or gay (or bisexual, transsexual, transgendered, two-spirited, questioning or intersex…).

I do worry, though, about the as-yet unbattered copy I’ve just released. The distances it may travel depend on those who happen upon it. What if it doesn’t get farther than one finder, and not because he or she likes it too much to let it go. Like all the books released by UVic, Daddy’s Roommate is vulnerable to misreadings as well as to the miserliness of hate. I can only entrust this copy to the hospitality that the burghers of the world are famed to have for strangers wanting a room (or bookshelf) for the night.

John Barton is editor of The Malahat Review

Views expressed in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect those of The Ring or the University of Victoria.