Like, your grammar’s amazing: research defends misunderstood word

- Stephanie Harrington

“I almost felt like I was cheated because I just like know how I’d act.”

University of Victoria linguist Alex D’Arcy wouldn’t be surprised if you thought that sentence was spoken in present day. The quote, however, came from a woman born in 1865, one of the earliest audio recordings of “like” used in this way.

Like, one of English’s most versatile words

D’Arcy, director of UVic’s Sociolinguistics Research Lab in the Faculty of Humanities, wants you to know “like,” a word most often associated with valley girls, surfers and teenagers, is one of English’s most exceptional and versatile words. And its varying uses stretch back hundreds of years.

“The word ‘like’ has a superpower; it’s able to do almost every job in the English language,” she says. “I can’t think of another word that behaves in that way. No other word has that flexibility.”

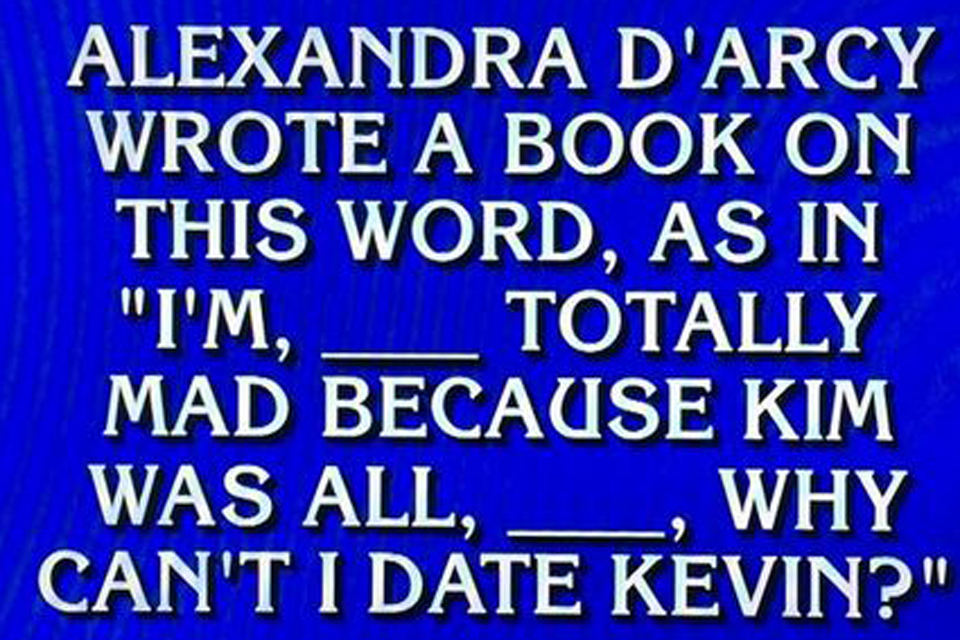

D’Arcy’s research, published in the first-ever book dedicated to the word, called Discourse Pragmatic Variation in Context: 800 Years of Like, traces its history in the English language from the 12th century to present day. Her research has been quoted in The Atlantic, to help explain a tweet from US President Donald Trump, and by the CBC. In March, D’Arcy’s name appeared as a clue on an episode of the famed TV quiz show, Jeopardy!

Like, know what I mean?

Contrary to the belief that “like” can be thrown anywhere in a sentence, D’Arcy’s work proves the word has rhyme and reason.

“Everybody uses ‘like,’” she says. “People assume you’re being vacuous and inarticulate when you use ‘like’ but using it actually demonstrates a complex understanding of English grammar.”

Some of the word’s uses are unremarkable—“like” has been a verb, adjective, noun, preposition and conjunction since Old English (think Beowolf) or Middle English (Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales) times. Much of her work focuses on two controversial and misunderstood functions of “like,” what linguists call a discourse marker and a pragmatic particle.

Discourse markers relate one sentence to a prior one, such as, “They never went out in a small canoe. Like, we went from here to Cape Beale.” D’Arcy says although people think this form of “like” is a recent phenomenon, the usage rose over the second half of the eighteenth century and has continued to today. (The example quoted comes from a woman born in 1875.)

Like, a Jeopardy clue

“The marker works like street signs. It shows you where the conversation is going.”

D’Arcy says the use of “like” as a pragmatic particle is often associated with young, typically female speech. Take, for instance, the Jeopardy clue, “Alexandra D’Arcy wrote a book on this word, as in, ‘I’m ____ totally mad because Kim was all _____, why can’t I date Kevin.’”

People started using “like” in what’s perceived as the stereotypical valley girl way in the late 1800s, D’Arcy says, with recordings from Canada, Australia, New Zealand and England proving its widespread use.

Valley girls didn’t exist yet. The Beat poets used "like" in this way before them. This "like" is used when you want to bring attention to a part of a sentence.

—UVic linguist Alex D’Arcy, director of UVic’s Sociolinguistics Research Lab

And new forms of ‘like’ continue to be created, with one of the newest variations, called an infix, becoming popular among young people. “That was un-like-believable,” D’Arcy says as an example.

Like, in the lexicon

D’Arcy says attempts to eradicate “like” from our lexicon, including a wikiHow page called “How to stop saying the word ‘like’: 10 steps,” are short-sighted and prejudicial against certain groups.

“It illustrates a lack of awareness about how language works,” she says. “It’s a dangerous form of discrimination, one that’s unchecked.”

It took time for D’Arcy to warm to the four-letter word. She started the research 15 years ago as a PhD student who wanted nothing to do with the seemingly frivolous topic. Now she fights against “educated snobbery” and sings the praises of “like” in all its glorious forms.

“I would never claim to be The ‘Like’ Person,” she says, “but I will claim to be a person who likes ‘like’ a lot.”

Public lecture on April 27

D’Arcy’s research is the subject of the Deans’ Lunchtime Lecture Series at 12.30 pm on April 27 at the Greater Victoria Public Library’s Central Branch.

UVic’s Department of Linguistics houses three labs—the Sociolinguistics Research Lab; Phonetics Lab; and Speech Research Lab.

These labs contribute in various ways to teaching and researching the phonetic and grammatical details of speech, from the physiological properties underlying speech to the acoustic signal that we hear and make sense of.

Find out more

Photos

In this story

Keywords: languages and linguistics, literature, research, writing

People: Alexandra D'Arcy