Mapping frog genome is huge leap in identifying environmental contaminant effects on thyroid system

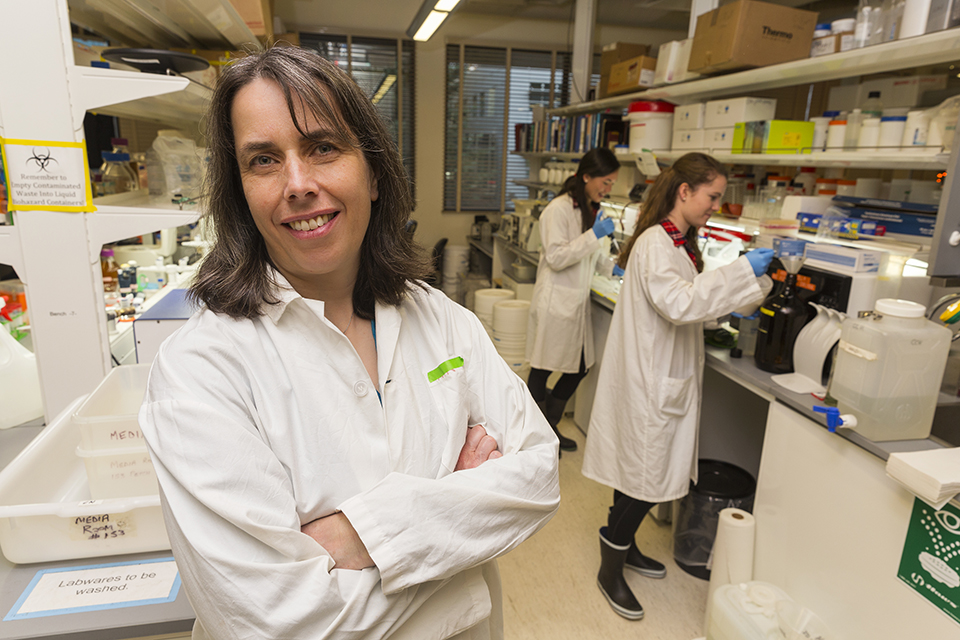

A University of Victoria molecular biologist has gained new insights into how environmental contaminants may disrupt thyroid systems, discovered while assembling the genome of the North American bullfrog.

Caren Helbing’s findings could help explain the mechanisms of early development and metamorphosis, as well as how environmental contaminants cause thyroid-related diseases and malfunctions.

While bullfrogs might be best known as invasive species in much of Canada, they are also vital animal models for scientific research.

“Understanding the mechanisms of gene expression in bullfrogs provides valuable insights with applications in human health, conservation and developmental biology,” says Helbing.

In order for a tadpole to turn into a frog, a genetic process is set in motion by thyroid hormones. Helbing’s research found that this metamorphosis involves thousands of non-coding genes. Unlike genes that code for proteins, which are the building blocks of life, noncoding genes are still a puzzle to researchers.

“The takeaway for human health is that non-coding genes may also be at play during early development,” says Helbing. “Understanding the mechanism of non-coding genes will help us understand how the thyroid system is affected during gestation, and how environmental contaminants can disrupt this process.”

Helbing’s lab is the first to map the full genome of any true frog–the family of frog species with the largest global distribution. True frogs are sentinel species, signalling by population distress or absence that there is environmental degradation.

“Two-thirds of amphibians are either threatened or declining. Some populations are being wiped out by diseases like chytrid fungus and ranavirus,” says Helbing. “Genomic information can help us determine what is happening, and how to stop the decimation of these species.”

Helbing’s results were published in Nature Communications last month. This work was supported by Genome British Columbia and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, with additional support provided by the National Human Genome Research Institute of the National Institutes of Health.

A media kit containing photos is available on Dropbox.

-- 30 --

Photos

Media contacts

Caren Helbing (Biochemistry and Microbiology) at 250-721-6146 or chelbing@uvic.ca

Vimala Jeevanandam (Communications Officer, Faculty of Science) at 250-721-8745 or scieco@uvic.ca

In this story

Keywords: wildlife, biology, biochemistry and microbiology, genetics, biomedical

People: Caren Helbing